I came up with the name for this newsletter largely on a whim. Daniel Neeleman aka Mr. Ballerina Farm shared an Instagram post about windows and I felt called to write about it; indeed, I wasn’t physically capable of NOT writing about it. I guess using the word “momfluencer” in the newsletter’s name would’ve been smart, but one of the most powerful images perpetuated by momfluencer culture has always been a clean countertop washed in sunlight. For me, in the context of the online performance of ideal motherhood, the clean countertop communicates cleanliness (obviously), order, domestic peace, a very specific kind of beauty, and the type of femininity “naturally” invested in making a house a home.

On Tuesday, I wrote about Julie D. O’Rourke (Rudy Jude). The essay is mostly about O’Rourke’s alleged connection to MAHA, but I also wrote about O’Rourke’s unique ability to create an image of home that is replete with implied values. Take a look at this photo of the interior of a CAMPER she and her family temporarily occupied.

There’s the vintage (or vintage looking) spackle bowl and literal oil lamp, showcasing respect for the good, strong things of the past. There’s the seemingly thrown together jar of flowers, implying effortlessness and a love of nature. There’s the WALLPAPERED walls, a ditsy floral pattern connoting a cozy sense of family. The addition of the wallpaper also shows off O’Rourke’s industriousness and refusal to live anywhere that doesn’t feel and look beautiful to her, which belies a strong sense of self and unwillingness to compromise. Even the red soda can (the label of which you can’t see, which is surely intentional) adds an aesthetically pleasing pop of color to the tableau. And of course, there’s the thick, golden sunshine bathing the entire image like honey. It’s all dreamy.

Momfluencers like O’Rourke are incredibly skilled at translating home into storytelling by way of imagery, but the imagery of home has little to do with the practicality of home, just like the imagery of motherhood has little to do with the actual labor of mothering.

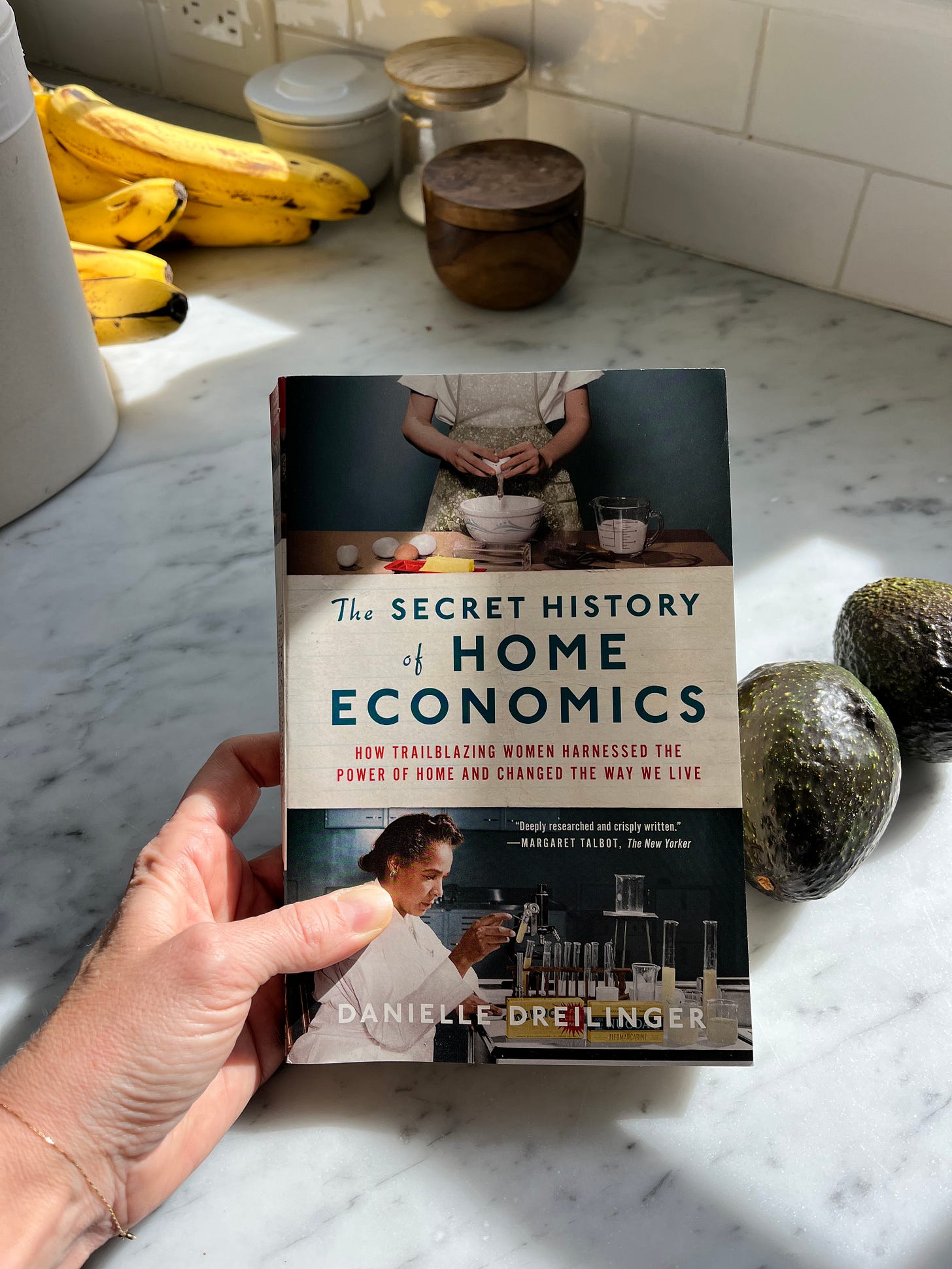

Before momfluencers, before women looking positively high from the joy of cleaning up spilled grape juice with Bounty paper towels, before June Cleaver, before home was weaponized as a symbol of capitalism and Good Motherhood, home was a site of scientific innovation and feminist revolution for home economists. And luckily for us,

wrote a truly astonishing book about the history of home economics - The Secret History Of Home Economics: How Trailblazing Women Harnessed The Power Of Home And Changed The Way We Live - which surprised me at nearly every turn.Home economics was a movement which started out as an opportunity for women to work outside the home AND to make lives easier for women working inside the home. And home economists are responsible for many organizations and innovations still very much relevant today. Home ec, a high school class in which some of us learned how to make CREAM PUFFS, is so much more than home ec. I promise you’ll never look at home or the economics of home in quite the same way again.

Sara: As is true with most things involving a large number of women, the vast majority of us know very little about the history of home economics. History is written by men, etc. I have a vivid memory of being taught how to make cream puffs (of all things!) in home ec, but until I read your book, I had no clue home economics was essentially a scientific movement led by women with the intention of making lives easier for other women. What initially triggered your research interest in the topic?

Danielle: Serendipity! I’d always wanted to write a book, and I had the opportunity to apply for a Knight-Wallace fellowship at the University of Michigan, which would give me a chunk of time to start. I wanted to write a book about education, because that’s what I was covering; history, because I’m a history buff; race, gender and class, because otherwise how would it be relevant; and – the X factor – I wanted to use the university library’s culinary collection, because one of the fellowship interviewers had mentioned it to me and I could practically see myself light up. I cook a lot (in the ordinary home cook way) and have read a ton of food writing, and figured writing a book might be more fun if it touched on one of my extracurricular interests. After a few weeks, I thought: “Home economics! The class that used to teach girls how to cook!”

Immediately I thought, “Why isn’t that back by now?” I had covered schools for a good four years at that point and hadn’t heard a lick about home ec – which is now typically called family and consumer sciences. A revival of home ec would seem to make so much sense given the interests in everything from craftivism to DIY decor to parents pushing back against standardized tests to the Food Network. And then the first thing I learned was that one of the founders was the first woman to attend MIT. At that point I knew: There is so much more here than anyone knows, including myself.

It took me at least six months of work on the book to remember that my mom was a business home economist – she double-majored in journalism and home economics, and worked in marketing at General Foods. A real facepalm moment.

Sara: For Momfluenced, I did a bit of research about not only the history of selling women and mothers on the idea of domesticity, but also the history of women taking homemaking seriously. The midcentury Betty Crocker campaign (helmed by one of the first female ad women, Jean Wade Rindlaub), as well as the work of late 19th century “home experts” (including a book written by Harriet Beecher Stowe and her sister Catherine Beecher, entitled The American Woman’s Home, or Principles of Domestic Science) were two really interesting examples of this phenomenon. In Rindlaub’s case, she shrewdly used her female identity to capitalistic advantage, and in the Beecher sisters’ case, they recognized homemaking as not merely a gender essentialist mandate, but as a highly skilled job. Can you share a bit about the intersection of capitalism and serious scientific inquiry as it pertains to home economics?

Danielle: Where even to start? First, to lay some groundwork: Home economics started as a field with two goals. The first was to liberate women from drudgery by making housework easier and faster – so they could do more important things with their time. The second was to create jobs where women would be accepted because these jobs had some connection, however tenuous, to jobs women had done in the home. For the most part, women couldn’t go to graduate school in chemistry – but they could go to grad school in home economics and do lab research on the chemistry of steak.

In general, these were women who worked within the system. The system being, of course, capitalistic. Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote about revolutionizing homemaking – she has a book about a woman who starts a maid service, What Diantha Did – but she was home economics–adjacent, a little too radical.

The early home economists were reacting to the Industrial Revolution, the wave of immigration in the late 19th century and the end of slavery. If y’all will indulge me, I’ll quote from the work of Ellen Swallow Richards, the MIT grad (and the university’s first female professor), a truly brilliant person who was ready to question everything. She recognized that the home was no longer the place of economic production, and women were being left behind, dependent on men who earned wages.

“The house and household affairs have not partaken of the marvelous changes of the 19th century . . . The flow of industry has passed on and left idle the loom in the attic, the soap kettle in the shed. The quick resource, the intelligent direction have been drafted into mercantile and manufacturing industries leaving the daily tasks relating to food and cleanliness, the dull routine work never done or only to be done over, to the less energetic and those content to drift.”

Home economists emphasized thrift, which isn’t exactly capitalist. Margaret Murray Washington, who ran home economics at Tuskegee and traveled the world talking about the Black family, edited a housekeeping handbook, Work for the Colored Women of the South, which was meant for sharecroppers who had almost nothing.

But! Starting after World War I, corporations began hiring home economists as marketing experts to reach women consumers – people like Marjorie Child Husted, who ran the Betty Crocker team. They saw themselves as educators who represented the customer to management. However, there’s no doubt they were part of a system that sold products. You sell a hell of a lot more Mr. Clean when you tell women they should mop the floor every day.

Sara: Speaking of Betty Crocker, we MUST discuss the various Betty Crockers across the country as well as the many “radio homemakers,” who might have been the proto momfluencers?

Danielle: Yes! General Mills had a radio program, then a TV program – it started as the “Cooking School of the Air” – where Betty Crocker shared recipes and, natch, promoted Gold Medal flour. Listeners could get a certificate if they sent in a card stamped by their grocer to show they used Gold Medal flour.

Betty Crocker was not a momfluencer: She was a professional! There’s a brand guideline doc I quote in my book that emphasizes the absolute requirement to keep Betty an expert: “She must stick to home economics and never discuss her private life, which would be rather dull anyway.”

Such radio shows went way beyond Betty Crocker. Home economists in extension quickly adopted radio as a way to reach the public; they too were professionals. It’s worth noting that until the 1970s, most home economists were not married and didn’t have children. The exception: Black women – because Black men didn’t have access to jobs that paid well enough to support a family, so there was always an expectation that their wives would work for pay.

The momfluencers of their day were what were called “radio homemakers.” Enormously popular. These were women who hosted radio shows where they talked about their kids and husband, shared household hints, cooked or baked dishes while narrating the recipes and just generally “visited on the air,” as the line went. They weren’t home economists, but they relied on home economists for a lot of their information.

To me, the most striking similarity to your modern momfluencer is the fact that these radio homemakers pretended to be Just Ordinary Moms when in reality they were – everyone together now – media professionals! They put on daily radio shows where they wrote scripts, ad libbed, shilled for products – they were working women. The first Black woman to host her own radio show in the U.S. was a radio homemaker, Willa Monroe, an impossibly glamorous kept woman (I’m not joking) who had a private chef.

Sara: What are some of the innovations we still enjoy today that came about because of the women of home economics?

Danielle: Clothing care labels, nutritional labels on food – home economists were passionate about educating the public. Nutritional breakdowns, period: Home economists created and published the first analyses of protein, fat, carbohydrates, etc. The food pyramid/MyPlate – in fact, the USDA Food and Nutrition Service is the remnant of the Bureau of Home Economics, which after its founding in 1923 employed more women scientists than any other entity in the country. Consumer protection laws, in partnership with other activists. The federal poverty limit, created by a home economist who worked at the Social Security Administration. The federal school lunch program – school lunch was a longstanding home economics project, because hungry kids can’t learn, and during the Depression/World War II/just after they teamed up with farmers to make it a federal project. Space food!

Pulling the camera back, you can argue that there wouldn’t have been anywhere near as many women college students, professors, businesspeople or scientists over the first six decades of the 20th century without home economics. At the time the field came under attack at Cornell in the late 1960s, three-quarters of the university’s women faculty were in the home ec college.

Then there are the efforts that didn’t succeed. Home economists promoted the metric system! They thought it was so much more sensible! Not wrong!

Sara: What role did home economists play during wartime? And relatedly, how was home economics a nationalist project?

Danielle: This takes up, I’m not exaggerating, three or four chapters in my book. Home economists played roles both on the home front – helping people survive rationing – and on the front lines, as dietitians for both healthy and sick soldiers. Martha Van Rensselaer and Flora Rose, co-directors of the Cornell home economics college (also, life partners), received an award after World War I for helping Belgian war survivors.

The nationalist project was far-reaching and complex. Also fascinating. Also infuriating. Especially between the wars, home economics was used to “Americanize” immigrants, teaching them the “right” ways to eat, cook and clean houses through public school, settlement houses and adult education.

Generally speaking, the women professionals in the field saw home economics as empowering, but men in charge could use it to keep women down. For instance, in the South you had districts where Black girls had an overwhelming amount of home ec to the detriment of academics. Some SoCal districts put Chicana girls in home economics because the white districts’ leaders thought they’d just become wives, mothers and maids. Sometimes communities pushed back. New York City had an actual multi-day riot after district leaders tried to implement a vocational-heavy curriculum.

After World War II, home economics became part of the U.S.’ international anti-Communism soft power project, with women establishing home economics colleges and taking part in various improvement efforts.

Sara: So many of the women involved in the history of home economics were true pioneers, but so many of their stories were new to me, and I suspect that’s because the stories of women who succeed in traditionally male fields tend to be more publicized in service of a feminist agenda. What do you think? And which women do you think (in particular) deserve more historical respect and renown?

Danielle: Hmmm. I don’t have an answer to the question of why these stories were lost – which they sure were; when Margaret Murray Washington died 100 years ago, she was so famous the President sent a telegram, and I have been enormously happy to see my work re-elevate her profile a bit – so I’m going to write a few notes that speak to the theme.

It’s interesting that one of the pioneering books I consulted was Margaret Rossiter’s multivolume history of women in science, in which she took home economists seriously as scientists.

The second wave of feminism looked down its nose at home economists – not because they thought those women weren’t succeeding in male fields but because the high school curriculum, by then, was sexist. Robin Morgan came to the American Association of Home Economics conference – by invitation – and ripped them to shreds. The field reacted with horror and just about immediately realized the ways in which they were promulgating sexist ideas – and changed. Morgan, for her part, was quite chagrined to learn well after the fact that home economists were progressive, professional pioneers.

The field has suffered in recent years because it is woman-dominated. (Well, also in the ‘50s through the ‘80s, but let’s stay focused.) The revival of vo-tech education focuses on well-paid, in-demand careers. The careers that came out of home economics are sure in demand: think of teaching, early childhood education, social services, restaurant jobs. But they pay terribly, because our society looks down on work that has traditionally been done by women and people of color. Is welding harder than teaching preschool? I, who can do neither, think not. But welding pays and thus it’s easier to promote as a career route for teenagers to consider.

Sara: Do you think that women selling to other women (whether it’s products or ideologies) on the basis of their personal experiences will always be more intrinsically powerful and compelling than any other mode of advertising or marketing to women? And if so, why?

Danielle: This is a great question I do not feel at all qualified to answer. I can only say that women selling to women has been incredibly powerful. Also women developing products: I’m reminded of a market research report Lillian Moller Gilbreth wrote – the mom in Cheaper by the Dozen – evaluating maxipads. She concluded that they all sucked because men designed them and were skeeved out by menstruation.

(Home economics sometimes included sex ed, too! Lots of ads in The Journal of Home Economics for Tampax’s classroom materials!)

Sara: How did the religious right manage to turn home economics into a tool of the culture wars? This is a GREAT reminder that the right has always recognized the power of weaponized womanhood and the power of family imagery when they’re politicized!

Danielle: Not just the religious right but conservatives in general. I spent a great deal of time and research considering why ‘50s and ‘60s home ec high school curriculum got so sexist, and I concluded that the key element was the introduction of child psychology – a field dominated by pediatricians and psychologists, mostly men. Before World War II, home economics textbooks presented childcare as a series of tasks that anybody could do. After WWII they had a touchy-feely emphasis on personal growth and interpersonal relations – and the claim that women, mothers, are better suited to bringing up children than men. (If women were natural mothers, would so many advice books exist?)

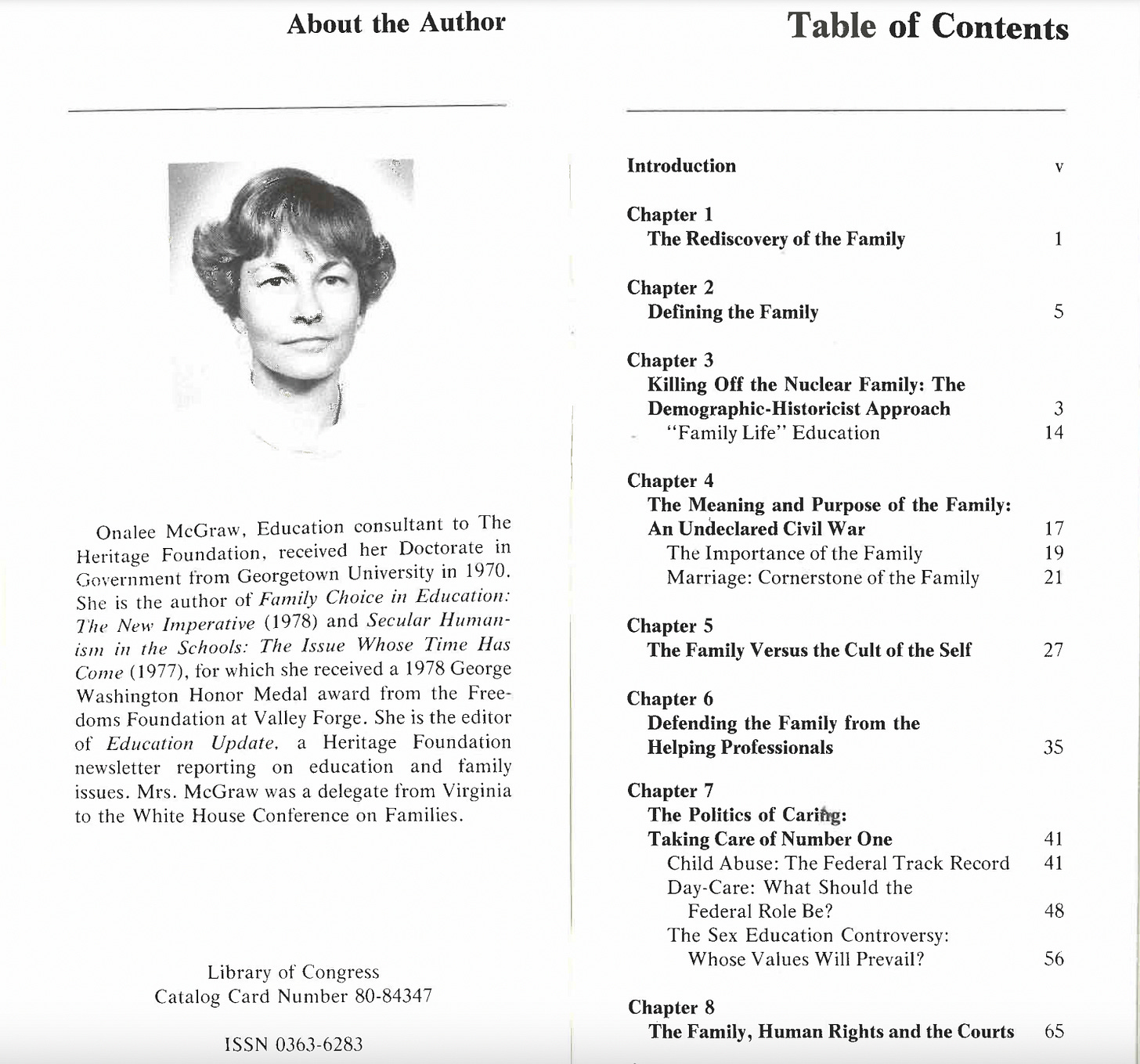

Later, after the home economics movement saw the second-wave light and began focusing on, e.g., getting women access to credit and helping divorced homemakers who were financially screwed, the religious right saw it as a threat. The Heritage Foundation put out a pamphlet saying home economists were destroying the family.

Meanwhile, the culture at large thought that home economics was an old-fashioned field that, uh, taught girls how to cook. So they just couldn’t win!

Sara: What now? I think many parts of the country would really REALLY love for the domestic arts to be taken seriously in public education. It’s such an invaluable way to teach children about gender equity, gender essentialism, and the vital importance of highly skilled (although unpaid and mostly invisible) labor. But many other parts of the country would love for women’s work to be strictly contained to the kitchen, the bedroom, and the home. And these factions crucially don’t want to view that work as labor: they want to view it as a gendered imperative. So what would a utopian vision of home economics be in your mind? And I guess depressingly, what’s the most we can hope for?

Danielle: During the writing process, every non-home-economics-person I told about the book reacted thus:

“I took home economics!” [Shares memory of a project they totally screwed up.] - or - “I wish I’d taken home economics!” + “We need to bring that back, because [kids don’t know how to cook/people throw away pants because they don’t know how to sew on a button].”

Home economics does still exist in school – again, look for family and consumer sciences – but it is certainly continuing to wane; it’s hard to get an accurate count because few states now have a person in charge of the curriculum.

There are all sorts of education-world challenges to getting home ec back into the school day. It’s hard to prioritize when kids struggle with basic literacy and numeracy. I’ve ended up telling people they need to advocate for the class at district and state boards of ed. What remains of the home economics field has sold the class as career preparation, which is a sensible strategy – they’re always trying to keep it from falling out of the federal Perkins vocational education act. That said, first, who knows what’s happening with federal education legislation given the Trump administration’s targeting of the Education Department; second, parents seem to be much more interested in the life skills component of home ec.

I do think that the COVID-19 pandemic opened the eyes of men in charge to the fact that the work of the home is work. All those mothers dropping out of the workforce, all those kids in the back of the Zoom window. It also cheers me that the boys I interviewed in home economics classes thought it was absolutely ridiculous that these skills should be considered the domain of girls.

As for utopian visions, home economics’ various philosophers have advanced lots of good ones!

Beatrice Paolucci and Marjorie Brown thought home ec should empower personal growth in the family and “enlightened, cooperative participation in the critique and formulation of social goals and means for accomplishing them.” Caroline Hunt wrote an astonishing and feminist vision of a better world in 1900 or so. And I think the American Home Economics Association’s definition from 1905, attributed to Ellen Richards, still has merit:

HOME ECONOMICS STANDS FOR

The ideal home life for to-day unhampered by the traditions of the past.

The utilization of all the resources of modern science to improve the home life.

The freedom of the home from the dominance of things and their due subordination to ideals.

The simplicity in material surroundings which will most free the spirit for the more important and permanent interests of the home and of society.

I loved this post! I grew up in Northern CA in the 70's and 80's, and at my jr high school the home ec class got rebranded as cooking. We didn't have a ton of electives, so there were more boys in the class than one might have expected for that era. Anyway, it was mostly baking and they did cover the chemistry aspect. I loved it and ended up doing lots of hobby baking as a teen and really liked the process of making stuff using chemistry. I majored in chemistry and got a PhD in it. Whenever I do STEM outreach to kids I tell them that cooking class was why I decided to be a chemist.

Also, big props to my PhD alma mater MIT and Ellen Swallow Richards. The chemistry department in the late 80's/early 90's was much more welcoming towards women than many other schools at the time, which was one of the reasons I decided to go there. In contrast, Caltech only started admitting female graduate students in the early 70's, and still had a lot fewer women 20 years later.

This article was so interesting. I’m raising 3 boys and I explain it like this, if your alive, eating, wearing clothes, showering, you know just living your life you need to be able to take care of all these human necessities. All chores are done by everyone in our home. I’d love some back up from the school side plus I see too many kids doing absolutely nothing to contribute to the functioning of their homes. I’m also thinking there is an environmental component to all this, being a responsible consumer, recycling etc. Thank you for such a great article. 👏👏