Finally - a definition of "authenticity" that makes sense of all the nonsense

Irène P. Mathieu on emotional overwhelm, hyper-individuality, and creating highlight reels of our lives

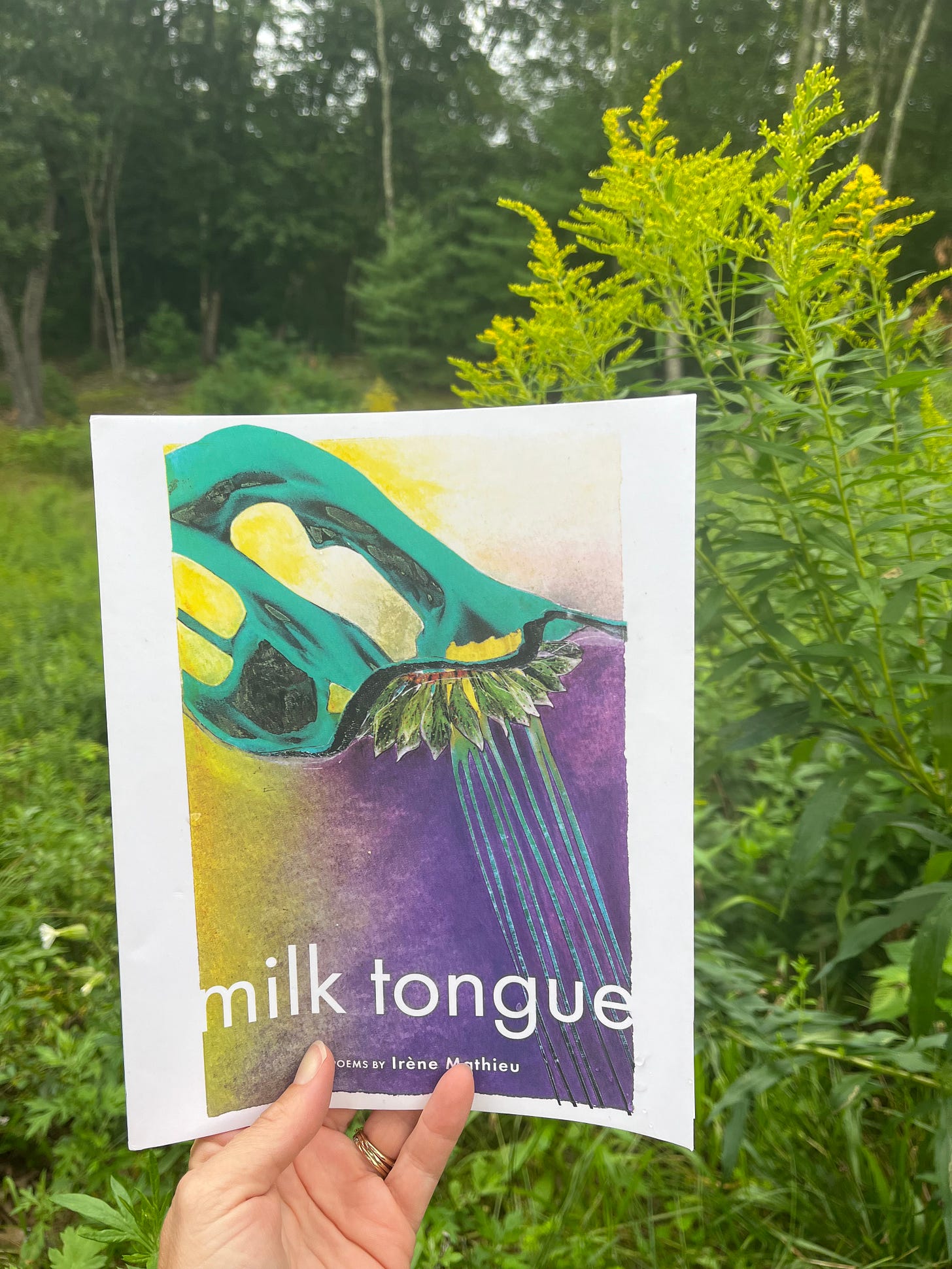

I would not call myself a big poetry person. I love certain poems. I savor poetic language (the last line of I Have Some Questions For You reverberated inside of me for a looooong time after reading it). But I’m not at all what one would call a connoisseur of poetry, and most of the poetry collections I’ve read and cherished have made their way to my bookshelf by way of a friend’s recommendation or a chance encounter with a gorgeous cover or an unforgettable title. Irène P. Mathieu’s evocative, unflinchingly curious, far-reaching milk tongue is no exception.

Irène P. Mathieu and I became connected through what used to be Twitter. I had thrown out an idea about a maternal performance panel for AWP (a big writers’ conference), and Irène responded to the idea and we “met” via email. Twitter used to be so great for these types of felicitous connections! The panel didn’t up working out, but if it weren’t for the randomness of the internet (and maybe kismet), I might have missed out on discovering (and becoming enriched by) Irène’s beautiful, nourishing work.

Irène is an academic pediatrician, writer, educator, and public health researcher. She is the award-winning author of four poetry collections – milk tongue (Deep Vellum Press, 2023), Grand Marronage (Switchback Books, 2019), orogeny (Trembling Pillow Press, 2017), and the galaxy of origins (dancing girl press, 2014), and she’s on Twitter here.

For me, reading milk tongue was like willingly climbing aboard a flotation device expertly comprised of words, images, and ideas. As I read, I thought about modern anxieties (and the look and feel of my own Anxiety), the shape-shifting nature of what we refer to as “home,” climate change, the make-believe of geographical borders, performing “authenticity” online and off, and what it means to mother, what it means to be mothered. It was an honor to be held by Irène’s poetry, and I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Sara: You do so many different kinds of work Irène. Could you talk a bit about the various professional hats you wear, how they all intersect, and how they’ve informed this collection?

Irène: I think about my overarching professional identity as that of a healer; I’m interested in how medicine, broadly speaking, and also literature can do healing work in the world. I do this as a primary care pediatrician and a physician-scientist who conducts community-engaged research on health inequities. I also teach medical students and doctors in training, both in clinical spaces and through health humanities courses, where I use literature as a teaching tool for future doctors. I do a lot of advocacy work around issues that affect child health equity, including climate justice, immigration policy, anti-trans and racist discrimination, and more. I’m also a poet, novelist, and essayist.

I think milk tongue is my first collection to explicitly invoke the medical and attempt to weave my professional worlds together more intentionally, but in all of my work the same central questions reverberate. How did this human world come to be, and why have we distanced ourselves so much from our non-human kin? How are my ancestors, living family, and I implicated in social inequities and environmental ruptures? How can poetry be applied as a tool for moving toward better health and life for all? What does language offer us as we imagine and work toward healing futures?

Sara: The title of your book, milk tongue, is a reference to the milky deposits on a breastfed infant’s tongue, but I read that you wrote the poems in this collection prior to motherhood, which surprised me since there are so many connections to mothering, being mothered, and caregiving. Can you talk a bit about how those themes emerged?

Irène: The themes in milk tongue emerged from the personal and professional questions of my life during the five-year period when I was finishing my medical training and beginning a career as a fully certified pediatrician, as well as moving, embarking on marriage, and considering expanding my family. I wrote the majority of these poems in the years before I had a child (but there are a couple of pregnancy poems toward the end of the book).

I’ve often heard it said that our poems are from the future, and I suppose writing these was a way of doing some of the psychic work I needed to do in preparation for becoming a mother. But I was also very interested in questions of nurturing, which I think is at the heart of mothering - how the Earth nurtures us and how we constantly fail to nurture it, how we might better nurture one another in human communities, nurturing between partners in the space of a new marriage, and nurturing our sweet dog, my first/fur child. I think nurturing is closely related to healing, and I probably associate these two in part because so much of pediatric medicine in primary care is about preventing illness and supporting children and families to grow into the best versions of themselves. So as a healer, nurturing is a big part of what I think I should be doing in the world, and maybe that’s why milk tongue feels like such a maternal book.

Sara: Home is a recurring subject in the book. You write about granular details of homes, broader geographic considerations of home, national definitions of home, and how a sense of belonging makes one feel at home. Did you go into the writing process intending to interrogate meanings of home, or did this happen organically? I’m also interested in how you’ve transformed “home,” something typically viewed as the provenance of women (and a solely domestic concern), into something so all-encompassing and something extending far beyond the domestic sphere and gender.

Irène: I’ve been writing about home for as long as I’ve been a writer! I think my questions about home – what and where it is, what we ought to expect from it, and what we owe it – arise from a feeling of displacement that many people of color in this country probably can share. I spent most of my childhood in Virginia, but my family hails primarily from New Orleans. I grew up hearing my grandparents’ stories of mid-twentieth-century Creole life, eating beans and rice and gumbo, and occasionally attending Catholic mass. I was (and am) constantly asked, “where are you from?” Culturally and socially, I never quite felt at home. There are many reasons for this, ranging from centuries of history to my parents’ somewhat unconventional child-rearing choices, but part of why I turned to writing in the first place was to create a kind of home for myself, even if only on the page. Now writing is a way to create home and belonging off the page as well; some of the poems in milk tongue are my first to explicitly attempt to do the latter. Home for me has always been about more than the physical structures in which we live and the domesticity inside these structures - it’s a political, social, cultural, and historical idea that informs the core of our identities.

Sara: In “stranded octopus syndrome,” you write (at least in part) about anxiety, and as someone who thinks quite a bit about authenticity and embodying the “real me,” this poem really stood out as being timely in our age of social media. I write quite a bit about the performance of selfhood (and the attendant anxiety that goes along with the performance) on social media for this newsletter, so I wonder if you could speak to that.

Irène: I think the notion of “authenticity” is so fraught. Even aside from social media, human beings are complicated creatures. We have multiple and sometimes conflicting beliefs, personality traits, needs, and desires that are all legitimate and true. I’m fascinated by the fact that our authentic selves can be so multifaceted.

The poem “stranded octopus syndrome” arose from the question of how I might grapple with the truth of my own complicated, multifaceted self in a way that might be helpful for others. I wrote about anxiety and other difficult emotions candidly in milk tongue because I believe vulnerability is critical to healing. We have to see the truth of what ails us – as individuals or as a society - before we can begin the process of repair. I think that part of my work as a healer is to model and practice that publicly. Everything intentionally shared in public - whether it’s art or social media posts - is curated, right? So my goal in sharing about anxiety is to create a space of vulnerability that my readers, hopefully, feel comfortable occupying with me.

Sara: In “Ode to smoked salmon jerky,” you write about salmon jerky. Ha. But you also write about the intermingling of the natural world and capitalism and colonization and industrialization and seem to be trying to make sense of this intermingling.

“Ode to the way I have looked at every

Image of a salmon since then with

New reverence, as evidence of order

That my whirring brain, my nearsighted

Eyes, were not made to understand -”

I think many of us, burnt out from productivity culture, structurally unsupported, and raising children during a climate crisis, are struggling to make sense of LIFE and (for me at least) this often leads to a sort of state of limbo within my own whirring brain. I’m not expecting any sort of definitive answer to this really, but do you find the particularities of NOW lending themselves towards individual existential crises, or do you think humans have always wrestled with LIFE NOW?

Irène: Those struggles are so real, and I share the various sources of burnout you identified! Humans have probably always wrestled with LIFE NOW, but I think the particular concerns of this moment are especially difficult to deal with because we are in the age of the Internet, so a massive amount of information is constantly available to us. We are exposed to the stresses and tragedies not only of our individual lives and those of the people we know personally, but also the catastrophes facing billions of other humans around the planet. And because of the multiple global crises facing us at this point in history there is no shortage of such catastrophes on our news feeds. This can definitely lead to emotional overwhelm that pushes us toward individual existential crises, as you say.

It’s ironic because I firmly believe that the (overly simplistic) answer to a lot of this overwhelm and the crises that have caused it is more and deeper connection with one another. More mutual aid, more deep listening, more collective action. The racialized capitalism that has led us to the climate crisis and other modern-day calamities thrives on hyper-individuality. The antidote to this is collectivity. In addition to fighting stress and overwhelm, collective action helps us move away from racist, capitalist structures in which the individual - and the nuclear family - have social primacy. So easy and simple, right?!

Mindfulness practices have also helped me with my “whirring brain,” and I think are deeply critical in fighting a state of constant overwhelm/exhaustion/panic/cynicism that often threatens to overtake me. I frequently remind myself that such practices are not a luxury; rather they are essential tools in maintaining the presence of mind/body/spirit necessary to be a decent parent, partner, friend, neighbor, and hopefully an agent of change.

Sara: In a poem called “the house,” you write the following:

The performance of living well is an intrinsic

Aspect of living well. Predating social media,

This ability to meta-experience one’s own

Experience is an inherent function of the human brain

And later:

Authenticity

Is a measure of the extent to which we are able to

pretend our performance is nonexistent - our ability

To perform non-performing

I don’t think I’ve ever read a more insightful definition of authenticity, particularly as it pertains to social media performance (or the appearance of non-performance). Why do you think we remain culturally obsessed with authenticity despite its apparent impossibility? And why do you think “authenticity” has become the golden standard for what we should all aspire to? Lastly (this is a many-pronged question) could you share some of your own experiences navigating “authenticity” in the age of social media?

Irène: Thank you! I suspect people’s relationship to the idea of authenticity, and its social importance, is highly culturally specific. In mainstream U.S. American culture, I really think a lot of it has to do with capitalism. We have been conditioned to think of ourselves as consumers, and we want to believe that what we are consuming is real, not a placebo or a sham. That’s the whole point of advertisements “with actual patients, not actors,” right? If social media is about creating a personal brand, then the last thing you want is for the consumers of your brand to see through it and understand that they are being sold an image that has been curated and crafted with a particular end in mind. People have to buy into the idea of a thing before they will buy the thing. So I think capitalism has taught us to more highly value (either by spending money on or devoting our attention/love/resources to) what we perceive as “real.” Maybe that's a cynical take, but that is my armchair sociology hypothesis. I am sure much has been written about this by actual scholars of American culture and history!

In the past few years I have found myself pulling back from social media. I worry about the harms perpetuated when we create a highlight reel of our lives, and on the other hand, I don’t have the time or emotional bandwidth to share all of the lows, too. Many of my highs and lows in the past couple of years revolve around parenting, but I feel extremely protective of my daughter’s privacy and have chosen not to share much content involving her before she is old enough to understand and meaningfully consent to it. And we both know how powerful the social pressures of sharenting can be. Parenting is so personal and so intense - I’m not interested in contributing to comparative or competitive dynamics around it, even inadvertently. So for me social media has become primarily a news sharing, advocacy, and professional networking space.

Sara: In “never have I ever,” you write about babies and desire and consumption and making.

Never have I ever wanted so much - eating ice cream at any hour, crying over the chorus

Of spring peepers Dopplering through the passenger window

Did pregnancy make you feel a different sense of desire? How do you think motherhood changes our perceptions of desire?

Irène: Oh, totally! I mean, there are pictures of me sitting on our couch at about eight-and-a-half months pregnant, eating double chocolate ice cream directly out of a gallon container because I had such a heightened appetite on a literal, visceral level. I had an elevated appetite not only for food, but also for life. I experienced the hormonal changes of pregnancy as a kind of heightened sensitivity to life - and it made me want more. I watched sappy movies because they made me cry. I felt more tuned into everything - I just wanted the world in this desperate way, maybe because in pregnancy I was making more world inside me.

That's not really a sustainable emotional state, but it made me think a lot about both the dangers of desire and its transformative power. I thought, maybe by being more emotionally invested in the world I can also access a deeper commitment to trying to change it. That probably sounds very pollyannaish, but now I have a child who’s a witness to my smallest, quotidian choices. For example, I can’t bring myself to kill bugs in front of my child. If I no longer feel it's appropriate to kill an insect in front of her, how might that choice to practice nonviolence impact other areas of my life? If we're talking about desire, it's a question of how badly I want the world - or even just my community - to be different. What am I willing to (not) do to walk that walk?

Sara: In “second attempt at going home” you write:

praise the woman who taught us how

To clean a bathtub well, how to saute garlic and onions

Like an invocation to the worship we’d do

In the kitchen. Praise anyplace you

Are well-fed. Here is one way to go home.

This passage is so beautiful, and I think I love it because we all carry domestic memories that make us ourselves, that have the power to root us in ourselves, and so often these memories are created by mothers. How can this type of mothering, this feeding of bodies, and nurturing of sense-memories be radical?

Irène: Sometime toward the end of my pregnancy, or maybe in the postpartum period, I read the book Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines. It's a beautiful, moving anthology of essays by mothers of color who are working, in a variety of ways, toward a more just and peaceful world. Their stories sustained me during that time, and made me think more about how those private, domestic moments - like the one from the poem you quoted - ultimately shape entire societies.

I try to be intentional in every moment, no matter how small, and I'm fortunate to have a partner who's equally committed to this intentionality. That's not to say I always respond to every situation the way I'd like, but I try to practice a mindful presence that allows me to be aware of how I'm reacting. That way, if I'm not proud of my reaction, I can respond differently the next time, or pause and correct myself. Which leads me to another book I've really enjoyed reading since becoming a parent - Everyday Blessings: The Inner Work of Mindful Parenting, which is a great introduction to this practice.

When it comes to social change, I think we are taught by society to minimize the daily domestic labor so often done by women, femmes, and mothers, and to over-value showier, more public forms of labor. But childhood is such a formative time, and especially those first few years. Any nurturing done during this time will have impacts on the rest of society later on, so this nurturing is a form of movement building. What if we seriously valued the labor of everyone who cared for and taught other human beings during this critical window? What if we honored that as some of the most important work there is, and organized our society around supporting the people who do it? In milk tongue I am, in part, trying to understand the value of nurturing, broadly speaking, and write toward being better at it.