Is a "balanced" relationship with your phone even possible?

Jessica Elefante says no.

I am a late adopter to pretty much all technologies because I am a sensitive, easily overstimulated person very much prone to FOMO, self-doubt, and imposter syndrome. I’ve always been wary of introducing any MORE input or complication into my life, and it wasn’t until I was pregnant with my first child that my sister essentially forced me to buy an iPhone so I could take decent photos of that baby. It wasn’t until that baby was a year old that I finally downloaded Instagram, mostly to have access to the Clarendon photo filter, which I used to saturate the purple of grape hyacinths in extremely of-the-time photos like this.

I joined Instagram so I could make my daily life look more beautiful. To the dozen or so friends and family that followed me on the app, sure. But mostly for myself.

Since those halcyon days of restaurant shots, skyline shots, and yes, smiling baby shots, my feelings about social media and the attention economy have undergone drastic shifts.

I spent several years trying to understand the relationship between my own perception of motherhood and the performances of motherhood I was consuming online, and ultimately turned this obsession into a book. And then I used Instagram to sell myself in order to sell that book. Rarely did the process spark joy! Mostly, the act of self-promotion momentarily tricks me into feeling a greater sense of control over my career trajectory than is possible. How many hours of my one wild and precious life do I really want to spend making reels in the hopes that it will inspire 2 or 3 people (at best??) to buy my book?

A compilation of my many 🙃 Thoughts and Feelings 🙃 about social media

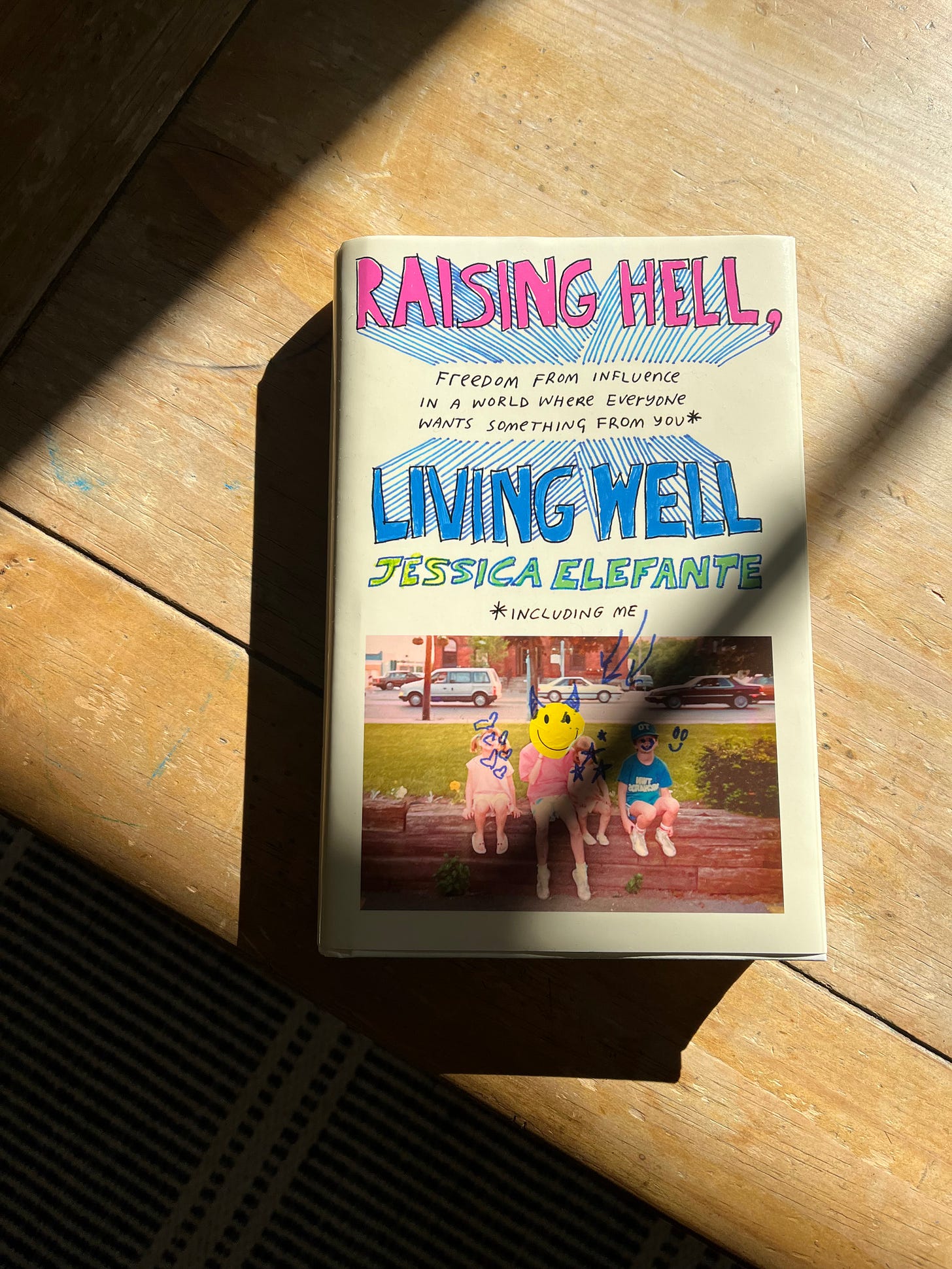

and I first became acquainted through this very newsletter! In response to one of my many “social media is destroying me” essays (see above) Jess offered a bevy of validation, her personal experience, and insight. So much so that I asked to interview her. We had a delightful chat over a year ago and I never got around to transcribing our interview and that’s entirely on me. But it’s FINE because today we’re talking about Jess’s brand new book, Raising Hell, Living Well: Freedom from Influence in a World Where Everyone Wants Something from You (Including Me) which is part manifesto, part cautionary tale, and all inspiring.

Here’s an excerpt I should absolutely learn how to cross-stitch onto something.

I am not your clickbait. I am not your ecourse guru, your Instagrammable motivational quote, or your #goals inspo. I am not the second image of a before/after meme–how it started, how it’s going. I am not your relationships-in-the-digital-age expert offering tips on “how to consciously uncouple (and still get half of what’s rightfully yours!”) I am not a live-feed reality show for you to slow-eat-popcorn gif while you laugh-cry-emoji my life falling apart. And I am not what is, or is not, broadcast onto pixels and screens.

Jess is a delight and her book will make you totally examine your relationship to influence, connection, aspiration, and time. As Margo Steines, author of Brutalities, writes: “Jessica details exactly how the sky is falling, walking us through experiences that resonate with familiarity until we, too, are urgently pointing skyward.”

Sara: Ok, I want to start by saying I have never been so utterly charmed by book swag! And as I was drooling over every item in your beautifully curated box, I kept thinking about how you might have approached this from a folk rebellion standpoint. Book swag is basically marketing, and marketing is primarily used to influence people to buy something. Your entire book (and personal ethos) is about deliberately understanding one’s cultural and individual influences and to cease making life choices based solely on the noise of unwanted influence. So tell me how you wrestled with not only book swag but the pressure to market yourself as an author. IT IS A LOT.

Jess: Oh I’ve wrestled. I asked everyone I know how I should handle the duality and irony. But I had to be the one to figure out how to thread that needle. And then one night it just hit me. I just have to be unapologetically me, about my apology. This book is my showing of the cards for the work I used to do to get people to buy things, buy into ideas/ideals/messaging/etc and so while I would like the work to speak for itself, I thought that maybe how I marketed it was also a case study in the tools at work. No tricks. No bullshit. I am putting the ask right up front. Buy this book. I made it and I am trying to persuade you to purchase it and read it. I’ve turned down MANY things that did not align with my values or its thesis. I will not be making small easily digestible pieces of content that the algorithm loves. I’ll be opting out of zoom events and focusing on IRL moments. If I meet someone online I try to grab a coffee with them. I’m choosing my colleagues, peers, press, affiliations with high touch kid gloves as opposed to being everywhere all the time at once. I hope that my intentionality builds trust with my readers. Fingers crossed. As for the swag, I just had fun with it. I wanted it to represent me and my book. I even make fun of myself. But also, I knew it was so unique that it would do what I wanted it to do. Fucking 10 cent pizza boxes and analog folded notes. Who knew? Me, I guess.

Sara: Can you share a bit about the term “folk rebellion,” both as related to your book and also as it relates to your prior business, and how the success of that business ultimately led you to completely recalibrate your life, your priorities, and your relationship to screens?

Jess: A decade ago I began a “mission” to “wake people up from their technology” because I believed that the way we were using it wasn’t the best way for us. Back then digital detox was barely even a term. Nobody wants to be told that they’re scrambling their brains (that was what happened to me) so I decided to lead (trick?) people into having conversations around our digital usage through a lifestyle brand. My intentions were from a personal place, my own addiction and all the ailments that came with it, and I wanted to fix things for my kids, make right what I contributed to creating. Folk Rebellion was my way of making my ethos very clear. It was countercultural in its intent and in its name. Folk as defined by the dictionary (I’m paraphrasing here) are the keepers of a traditional way of a society or culture. Folk music, folk art, folk stories for example. But Folk is all people. Often defined as simple, open hearted people. I thought the use of Folk was the ideal term for making this an invitation to community and also a rallying cry. I wanted people to keep our human traditions and push back on the tsunami of the digital wave that was about to consume us all. And it took off pretty quickly. People were desperate for permission to say they hated being ignored by their partner, answering emails at 2am, always being available and the instant gratification of, well, everything. I’m proud of the work I did with Folk Rebellion, helping usher forward this sort of digital wellness zeitgeisty conversation that's more prevalent today. But in the end I just ended up recreating the same issues I’d had in corporate America. I was striving, working too much, always connected, and pouring myself into others' motivations and under the influence of the cultures I had grown up with. It was an epic crash and burn. Shuttered the business, dissolved my marriage, hid away for a few years trying to process it all. At the other end of it I realized that it wasn’t just tech and the digital world. It was the culture of influence.

Sara: I’m often asked about my own relationship to social media, and it always pains me a little to say that if I could quit it entirely I would. I have absolutely made friends through social media, learned things, and expanded my perspective, but the routine usage of social media mostly just depletes me. I’m encouraged to see many thinkers (like you!) seriously tackling what I view as one of the biggest issues of our time: our relationships to devices and the attention economy. I wonder when we’ll see more widespread consideration of social media addiction, IRL loneliness, etc. Or if? Or how?

Jess: This was one of my rock bottom moments. I had been preaching that we can have a mindful relationship with technology for almost a decade. I believed we could have balance. I felt moderation, awareness, tools, tips, and tricks were the way. That we just needed to become aware of how it worked, and make it work for us. I no longer believe that. That’s a hard thing to say especially for someone who whole-heartedly believed it and espoused it to everyone. But when I look at the influences of who’s behind the devices, platforms, algorithms, and the structures that allow them to operate the way they do, I can see clear as day now that, no, we cannot have a mindful relationship with our technology. I talk about this in the book but the solutions I was suggesting at the time of Folk Rebellion laid the responsibility at our feet, as if we (the humans/users) were the problem. Our addictions, loneliness, sadness, anxiety were all our own to handle. I now believe that the only way to ever have any positive relationship with our tech, devices, AI, whatever else comes next, is to lay the responsibility at the feet of its creators. Regulation. And unfortunately for us, our regulators, government, politicians, private equity funders are all under influences of their own. And we all know what that is, right? It’s only with immense communal pressure from the general public TOGETHER—that we ever have a chance of having tech and digital that doesn’t harm us. It’s too profitable to trigger our innate instincts.

Sara: I am obsessed with guru culture. Gurus have always capitalized on people's fears, insecurities, and desires, but social media has made it REALLY easy (and profitable) for all sorts of people to set themselves up as ultimate authorities. You write that “the problem here is the pervasive idea today that we all need to be better.” We are so conditioned to view endless self-optimization (whatever that means) as being good and right. Can you talk about that mindset and how guru culture both upholds and perpetuates it?

Jess: Decades ago I started reading The Idler, a publication out of the UK that is like 90s slacker culture and pre-industrial revolution idealism and it changed the way I think in terms of improvement. Prior to discovering The Idler, I was a disciple of Zig Ziglar and Tony Robbins. It was lost on me at the time that I was glugging the motivational guru's ideals they were selling—that I can improve, mastery is around the next corner, one more rung and I can manifest this . . . etc. It was a movable carrot and one that always promised some fulfillment after something. That something was always positioned as something I needed to change, tweak, make better. Not a huge life altering swing, but just bits of improvement, because if I just dressed a little sharper, stood a little taller, studied a little more, then maybe I could get X . . . whatever that was for me at the time. Sometimes it was money, sometimes love, sometimes purpose. But that’s the thing right? There’s always a next thing, a little something more. The Idler really helped me deprogram my thinking about efficiencies, productivity, achievement, time, and purpose. It allowed me to see the influences that were profiting from my hamster wheel of optimization and opt out.

Sara: Part of what I find so existentially upsetting about influencer culture in general (and momfluencer culture in particular) is the commodification of vulnerability, of human pain. One of the momfluencers I interviewed for my book told me about talking to prospective agents and managers, and them coaching her to “always record yourself crying if possible” because tears and “vulnerable disclosures” increase engagement, which could lead to more followers, which will make you look more attractive as a business partner to brands. How do you think modern life has perverted words like “authentic” and “vulnerability"?” Shout-out out to the 1,274 contestants on both The Bachelor and The Bachelorette who have been praised for sharing their trauma with people they met a week ago (and millions of viewers) in the name of “getting vulnerable.”

Jess: Again, the unscrupulous bastards who are profiting off us by exploiting us—whether that be our data, our tears, our attention, our security in our body, our time, our money, our future, I could go on but you get the point—are never going to do right by us unless we band together and force them to. It’s only in opting out, not giving them our dollars and eyeballs and tears, that we stop rewarding the bad behaviors. The algorithm pushes what’s watched. What’s watched pushes people to conform to the behaviors of what's watched, if they care about their engagement (which they likely do because they’ve been trained to do so). What was once something that felt outrageous becomes acceptable over a thousand little cuts.

Sara: While OF COURSE, people of all genders are addicted to their phones and shallow hits of dopamine elicited through likes, hearts, and retweets, I see a connection between the way we talk about social media addiction and the way we talk about motherhood. Just as we’ve normalized surface level conversations about mothering hardships, we’ve also sort of normalized the toxicity of certain aspects of technological influence. Like, how many times have you heard a group of moms vent about their inept partners or their burnout but laugh it off as if that was just how motherhood had to be? I feel similarly about the way we talk about our tech. Like, “My phone owns me and it’s terrible but that’s life!” What sort of systemic forces make it so easy for us to sort of accept and internalize our powerlessness in the face of tech? And do you think any of these forces overlap with the structures making mothers’ lives difficult?

Jess: Oh for sure. Capitalism, commercialism, consumerism, and commodification (the 4Cs, as I call them in the book) limit our happiness, freedom, and wellbeing. It’s difficult to opt out when our schools, governments, healthcare systems are all operating as if this is normal and to be accepted. Instead of providing protections or limited use until, say, a tech company proves that their whatever it is (edtech/device/app) isn’t harmful, we operate under a capitalist system that prioritizes minimal government intervention and protection of private property rights. Sounds great in theory but what these pillars have enabled is the creation of colossal companies with little to no government regulation. Corporations have, of course, learned how to manipulate both the right to privacy and lack of government in order to exploit the people—us. What we are experiencing now is a society and government that's been under the influence of capitalism for so long it favors protecting it above all else, even when it's being exploitative. Harming us. I know, I’m a ball of fun.

Sara: What most surprised you about reevaluating your relationship to social media, influence, and technology?

Jess: That it wasn’t just about technology, it was the culture of influence in everything. Living an intentional life is less about self help, minimalism, and digital detox retreats and more accessible than we think. It's not tricks, tasks and lifestyle changes, it's a shift of mindset in how we view the world.

Sara. Thank you so much for featuring me and my book here! Your community is brilliant!

Wonderful to read more about Jess after getting to know her work via @danblank and admiring his reaction to the pizza box too. Thanks to both of you for continuing to call out the effect of what we unconsciously do online. Great post.