"It's called Ballerina Farm not Hip-Hop Farm or Jazz Farm"

On ballet, whiteness, and the privilege of messiness with Chloe Angyal

I’m back on my bullshit today with some Ballerina Farm analysis, and I’m excited because this particular flavor of analysis is born not from my own personal preoccupation but from an external suggestion.

Back when I wrote my inaugural newsletter about the window everyone loves to hate, writer and PhD Chloe Angyal slid into my twitter DMs with this tantalizing message:

If you ever want to chat with me about the ways ballet is representing and reinforcing whiteness, I would be down for that!

And obviously my answer was: “HELL YES.”

Because wow. I’ve consider many facets of the Ballerina Farm brand. I’ve considered the performance of authenticity, I’ve considered the pageantry, I’ve considered Agnes the Aga stove, I’ve considered the aesthetic and ideological function of BF baby names, I’ve considered if I should be writing about Ballerina Farm at all, and obviously, I’ve considered how @ballerinafarm upholds and perpetuates the myth of the ideal mother.

But I have never considered the ballet.

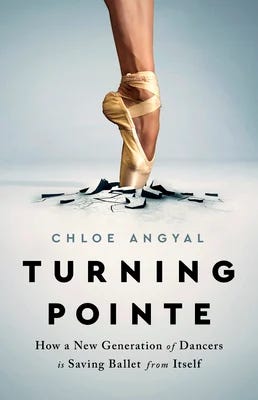

Chloe Angyal is a journalist and author of the book, Turning Pointe: How a New Generation of Dancers is Saving Ballet from Itself, and is currently working on her first novel, Pas de Don’t, a romance set in the ballet worlds of New York City and Sydney.

Chloe and I chatted about the Ballerina Farm logo, the history of ballet as a white institution, and how Ballerina Farm’s band is built on both the performance of ease and the performance of labor. Here’s our conversation, which has been edited for clarity.

How did you first come across Ballerina Farm?

I think it was the interview between Anne Helen Petersen and Meg Conley. And I was like, this is really interesting but why aren't we talking about the ballet part of Ballerina Farm? Because it's doing a lot of work here that no one seems to be talking about. Like, yeah, there are the babies and the pigs and the JetBlue husband, but let's talk about the ballet part of Ballerina Farm because it's really important.

Okay, so let's talk about ballet!

First of all, it's Ballerina Farm, right? It's not Jazz Farm. It's not Hip-Hop Farm. It's not Tap Farm. It’s Ballerina Farm. We are talking about the whitest dance form that exists. All those other dance forms were originated by people of color, mostly by Black people. Ballet is the whitest art form, both in practice and also in the public imagination. It’s also really important to remember that it's not Ballet Farm. It's Ballerina Farm. We’re talking about the feminine person version of this dance form. We're talking about the pinnacle of a very specific kind of womanhood, a very specific kind of femininity.

And then there are all the other roles Hannah’s inhabiting, right? She's a mom. She's LDS. She's rural. She's a farmer. These are all positions that are heavily coded white in the public imagination. But I don't think any of those roles are more uniformly coded white than ballerina. So I don’t think you can talk about Ballerina Farm without talking about ballerinas and whiteness. And all of the symbolism that she's leaning on in the branding and in the presentation of her life online.

Can you talk a little bit about the history of whiteness and ballet?