The Unbearable Romance Of Dirty Dishes

Why is savoring the act of cleaning a measure of my motherhood?

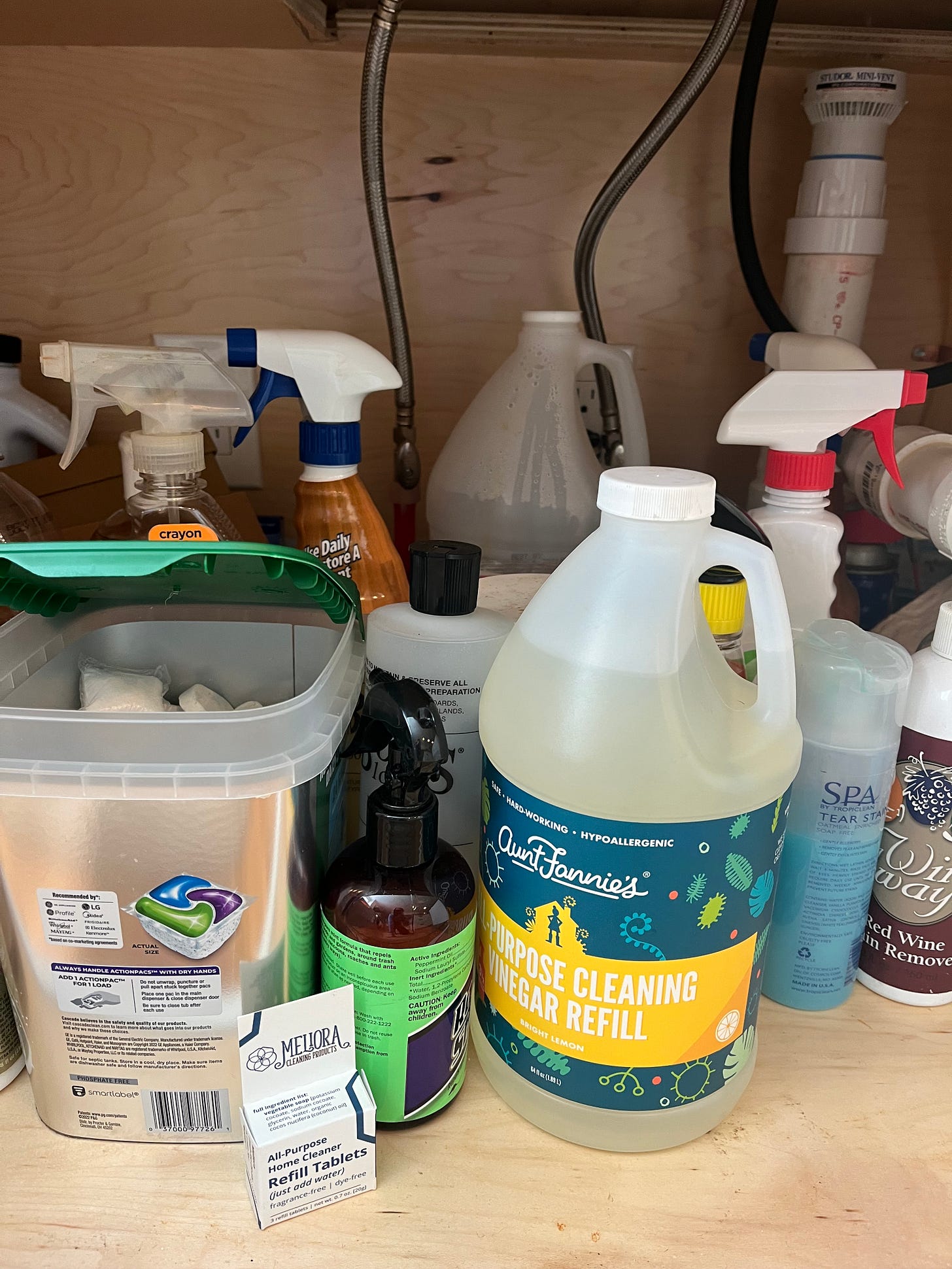

This is a photo of the cleaning products under my kitchen sink.

The cleaning products under my kitchen sink are used to remove hot dog grease from plates, to disinfect bathroom tiles after a middle-of-the-night vomit spree. They’re used to wipe away peanut butter smears, to scour burnt cheese from lasagna pans, and to eradicate the scent of dog pee.

This photo of the cleaning products under my sink is representative of the act of cleaning. It’s a utilitarian photo of a utilitarian, everyday act. It has nothing to do with aesthetics and everything to do with function.

But there’s a corner of the mamasphere that wants me to believe that cleaning can be something else. It can be slowing down. It can be living intentionally. It can be savoring the little moments.