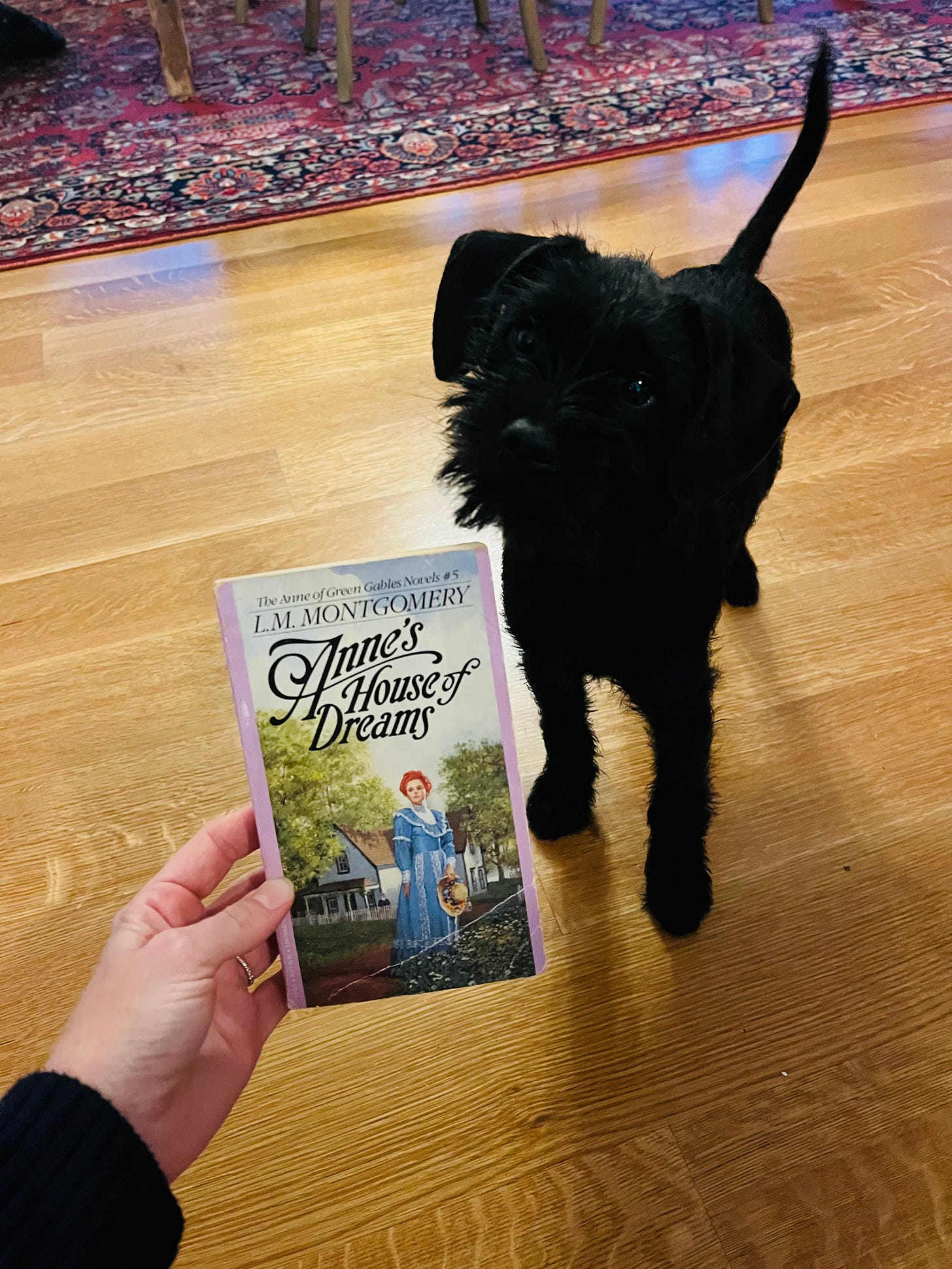

As a millennial teen, I pored over books featuring romantic 19th century heroines who experienced the technicolor drama of The Love Story before basking in the happy ending of motherhood and domesticity. Anne Shirley starts out as a fiery girl full of rage, but quickly mellows out into Mrs. Gilbert Blythe, reveling in her motherhood and the work of making a house a home. By the last couple of books, Anne is neatly confined to the background of her children’s lives.

And this narrative felt calming to me as a teenager, safe. I’m embarrassed to admit that the idea of Anne Shirley (sorry - Blythe) reigning supreme in her various domestic kingdoms also led me to feel dissatisfied with my immensely privileged lot, simply because the marriage plot sounded easier (and cozier?) than my future as a girl raised in “post-feminist” 90s grrrl power. My future demanded the hard work of self-actualization, the need to identify and work towards career goals, and the bewildering mandate to “follow my dreams.”

When you’re young, sometimes all you want is for someone to show you what you should dream. And if that dream is transmitted every hour through a little rectangle typically resting in the palm of one’s hand, it’s probably more palatable to buy into the dream rather than spend time pursuing logical fallacies or poking holes in the dream’s foundation. For me, as a sheltered white girl unthinkingly longing to achieve a domestic goddess fantasy, I didn’t interrogate who had access to the cult of domesticity, or who such a fantasy empowered and disempowered.

It’s not hard for me to imagine myself as a Gen Z girl coming of age in the Era of Trad, consuming fairytale narratives of insular feminine fulfillment and finding them more appealing than striving to make the best of a broken, unjust world. Especially today, when an active commitment to progressive values requires constant work, constant setbacks, and constant heartbreak.

10ish years ago, I was teaching freshman comp at a local university, and one of my students wrote an impassioned paper about how feminism was, for lack of a more expressive word, bad. She wrote vaguely about bra-burning and miserable, humorless women dissatisfied with their “unnatural” lives. She expressed frustration about limited options in the job market, and she argued that her dreams of motherhood and wifehood were no longer respected as viable dreams. Not the way they used to be, she claimed.

10ish years ago, I read this paper and felt depressed. But I also felt a spark of guilty connection with my younger self. I read between the lines of the anti-feminist propaganda untethered from historical reality, and saw the writer’s real thesis: she was afraid of her future. She was unsure of her future. What she wanted more than anything, it seemed to me, was clarity. 10ish years ago, #tradlife was not a thing. Nobody knew who Hannah Neeleman was. But 10ish years ago, young women like my college student were already feeling disillusioned with modern womanhood. And now, tradwives are here to speak to those women.

The trad mom promise of a "perfectly balanced world"

As part of my final Momfluenced edit, I updated the follower counts of all the momfluencers mentioned in the book. Depressingly, the follower count for every single alt-right/Q/trad mom mentioned in Momfluenced has gone up since I finished my first draft of the book in April 2022. When I first started researching the book back in 2020,

Tradwives have been accused of many things. Being complicit in their own oppression. Cosplaying domestic submission while actually working full-time jobs as content creators. Capitalizing on their allegiance to white supremacy instead of joining the intersectional feminist crusade to abolish white supremacy. Touting explicitly racist and misogynistic ideas about the extermination of childless cat ladies and raising armies of white children to ensure the domination of white power.

Taylor Swift Is Breaking Tradwives' Brains

The right has long struggled with what to do with Taylor Swift. Swift is white, blonde, thin, and marketably attractive. She loves a red lip, embraces femininity, regularly fucks around with a cottage core aesthetic, and many of her most famous songs feature princessy love stories which presumably end at the storybook [Christian] altar.

But in the wake of Trump’s victory, perhaps we should also give tradwives credit for galvanizing millions of young women to vote seemingly against their own interests, for a handful of powerful white men that want to make America great for a handful of powerful white men . . . again.

For Bustle, I wrote about how tradwives’ guidebook for a life well lived are prompting many Gen Z women to reject Cheryl Sandberg’s exhortation to “lean in” to the workplace in favor of heteronormativity, domesticity, and a commitment to traditional wifehood and motherhood. These young women are choosing financial dependence on a man, they’re choosing “freedom” from the near impossibility of balancing a career with domestic life.

And a shocking percentage of them actively chose Donald Trump.

On the one hand I can empathize with the current disillusionment of Gen Zer ladies looking at us burnt out (whether from career, motherhood, or a combination of both) millennials. I understand seeing all of our complaints and deciding, “well, I’ll just opt out of that!” But it makes me so completely sad because they’ve obviously missed the inherent flaw in that logic. I believe many of us were told the same message exhaustively: don’t rely on a man; you have to rely on yourself. And we believed the people telling us this because we *saw* the damage that had befallen women who had relied on a man. The first wife who supported her husband through medical school and then got left for a younger version of herself. The one who had a baby right out of high school and by her mid-20’s looked like she had lived 10 lives already. The mom who dedicated her life to her kids, then after the divorce had to work tirelessly to pay for a crappy apartment while her kids went to Dad’s McMansion on the weekends with the new girlfriend and the nanny. There are reasons we chose to make ourselves miserable in this “new” way of not accepting anything less than full independence. And I’m afraid those reasons have been erased/whitewashed/explained away.

I will forever be mad about that line in Anne's House of Dreams (I think?) where she says her pupil Paul was a 'true poet' and she 'only imagined silly stories' (or words to that effect). The ONLY difference between Anne and Paul is that Paul is a boy. His 'poetry' is basically identical to what Anne said as a kid. Some readers argue that Anne's real dream was a home of her own, and maybe it was to some extent, but early Anne also had an imagination and dreams of writing.