Content warning: This piece is about childbirth and birth trauma of all kinds, so if that’s not for you today, I totally get it, and take good care.

Yolande Norris-Clark is a free birth influencer. Together with her frequent collaborator, Emilee Saldaya, she’s been selling free birth as gendered transcendence for several years. Norris-Clark claims that free birth is a “birth [that] is normal, spontaneous, natural, beautiful, and designed to be simple and blissful.” As far as I can tell, “free birth” in her view is birth ideally unmediated by modern medicine, and in which the birthing person is the only expert.

So, if you long to attain your destiny as a “real woman,” or if you want to live in your divine feminine power, or if you simply mistrust the western medical establishment, you can buy your way to a free birth of your own through any number of online courses, retreats, one-one-one counseling sessions, ebooks, or supplements. Central to most free birth influencers’ ideology is their belief that women are “made” to give birth, and that western medicine has conned us all into paying for something we can “naturally” do ourselves. And for unnecessarily complicating something intrinsically simple. But even amongst free birthing influencers, nothing is really free in the United States, nor is anything often simple. Even “pain-free blissful births” cost money. And they’re complicated.

Before I continue, I want to unequivocally say that birth is a highly intimate, entirely personal experience, and there’s no one way to conceptualize or experience it. I support any birth in which the birthing person is treated with compassion, respect, and given bodily autonomy. This can look any number of ways, and there is no such thing as a universal “good” birth.

I first stumbled upon Norris-Clark sometime in 2017 or 2018, and wrote about her (and others) in 2021. What instantly struck me about her (and still does) is the mantle of maternal warmth she wears alongside incongruously rigid commandments about childbirth (and life). She’s all smiles, light and love, even as she insists that hospital births sever the mother/child attachment, or that “industrial obstetric birth is a cult initiation rite,” or that a hospital birth is “satanic ritual abuse,” or that it’s “trauma-based mind control.” Or that feminism is about hating men and poses a danger to your children, or any number of transphobic beliefs.

Birth trauma is real, and traditional western medicine has a violent history of racism, ableism, and classism. Throughout the history of modern obstetrics, male practitioners have sterilized women without their consent, conducted painful, invasive experimental procedures on women without their consent, and caused significant harm for both people giving birth and their babies. Norris-Clark and her peers ground their mandates and ideologies in the reality that women have been historically mistreated by misogynistic birth “experts.”

From this truth though, Norris-Clark veers steeply into transphobic, gender-essentialist, and conservative rhetoric. “Real women” are “meant” to have babies. Feminism is a “destructive” force, birth control is antithetical to the “spontaneous cadence of biology,” and men and women are not equal. Patriarchy is awesome actually. According to prominent free birth influencers, the decision to have a child is less a calculated assessment about one’s own life, but [correctly] following one’s destiny to its “natural” conclusion. While free birthers might present as aesthetically liberal, they have more in common with the pronatalist activists who want to replicate the Nazis by awarding women medals in accordance to how many children they birth.

Norris-Clark has had ten “perfect free-births,” and is now pregnant with her eleventh child at 44. Because she lives in a place of unshakeable certainty, she does not fear her eleventh birth, nor does she believe that any woman should fear theirs. Not if you’re doing it right.

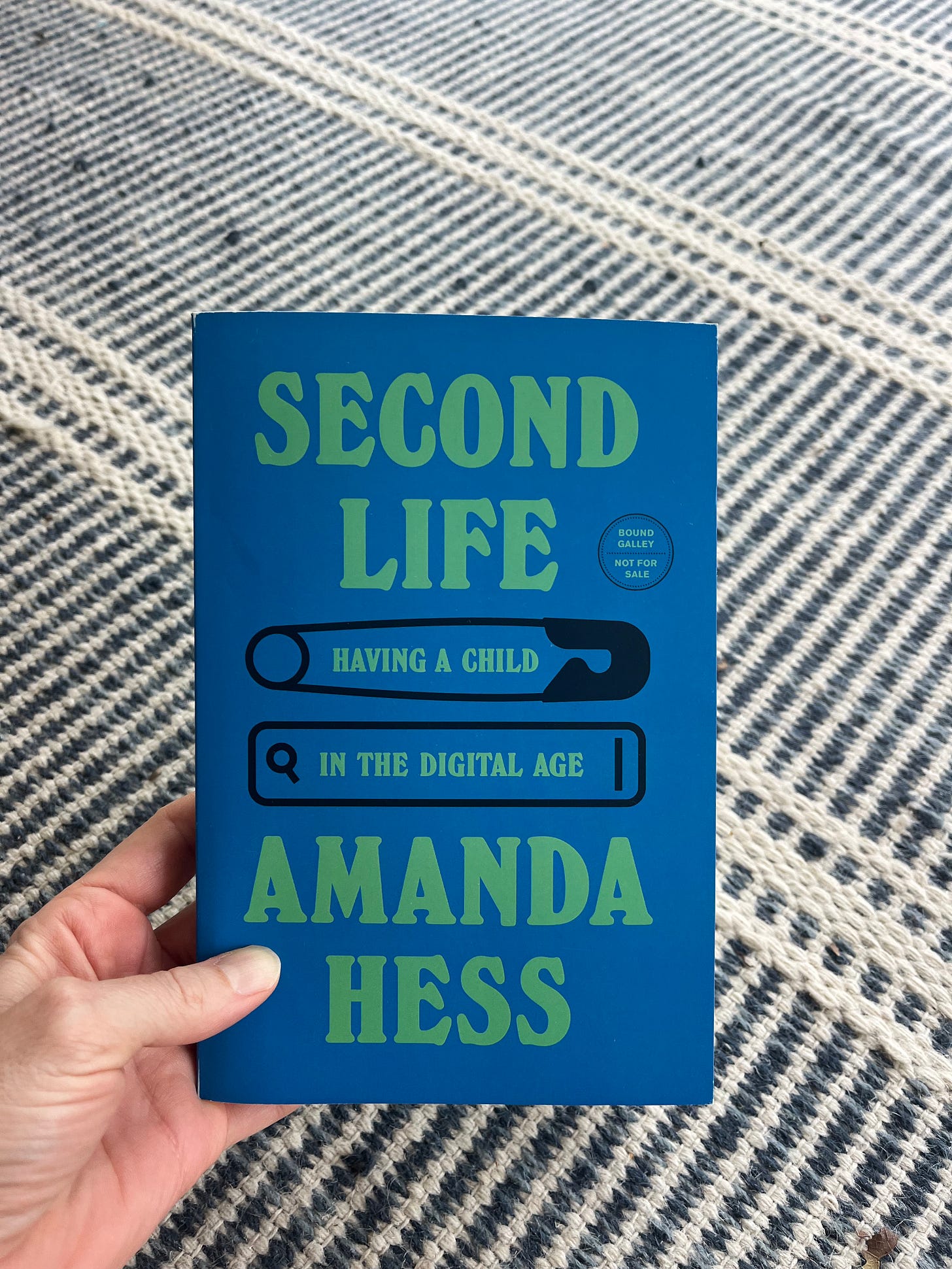

In her new, excellent book about the modern experience of experiencing motherhood mediated by technology, Second Life, Amanda Hess writes about purchasing one of Norris-Clark and Emilee Saldaya’s products, The Complete Guide To Freebirth. It’s a compilation of hundreds of videos of either Norris-Clark or Saldaya giving lectures about various birth-related topics.

In response to the question of safety, Saldaya says that birth has always been a life or death experience, and that modern medicine wants to trick us all into an illusion of safety. Hess quotes Saldaya saying, “‘I came to the conclusion that I would actively choose to be in my own intimate space even if the outcome was death . . . it was more important to me to receive my baby into my own hands, unmediated by machines and strangers and bright lights.’” When it comes to complicated deliveries or unexpected health challenges for either birthing person or baby, Norris-Clark glibly suggests that you will be able to confront any sort of emergency after absorbing the lessons of the Complete Guide To Freebirth. To illustrate this “fact,” she shares a secondhand story of a baby born at home with gastroschisis, a condition in which the baby’s intestines form outside of the baby’s body, and which requires immediate medical intervention.

Hess describes Norris-Clark giggling as she fails to correctly pronounce gastroschisis before soothing the anxious birthing person’s fears with this tidy anecdote: “‘I know of one family whose baby was born at home with . . . gastro . . . skis-skis . . .and whose birth attendant wrapped their baby’s organs and body in saran wrap, and immediately transferred to the hospital, and the baby was saved and survived. And so, we just don’t know!’”

But as Hess recounts in her book, sometimes we do know. For all its flaws and biases, sometimes life-changing information and treatment stems directly from modern maternal healthcare. Hess learned about her first child’s health condition when he was still in utero, and unlike Norris-Clark, did have firsthand experience with the anxiety, fear, and feeling of destabilization that came with a prenatal diagnosis. Hess also planned her birth accordingly, doing her best to ensure specific kinds of care. In light of this experience, Hess reflects on Norris-Clark saying she wants to give babies “‘the most intimate and authentic experience of life’ . . . but all she had to offer my baby was a laugh and a sheet of plastic. His little body wrapped up like a day-old deli sandwich.”

Racism has always informed modern conceptions of birth, and Black women in particular have every reason to approach a hospital birth with wariness, but the online free birther space is overwhelmingly white.1 Violence towards Black birthing people is embedded in American medicine, so one would think anti-Black racism would be a primary concern for free birthing influencers. White doctor James Marion Sims conducted medical experimentation (without anesthesia) on enslaved Black women in the 1840s and defended his actions by arguing that Black women did not feel pain in childbirth, a myth which continues to inform Black patients’ natal care today. But in the white free birthing space, there’s very little focus on the most vulnerable birthing people in the U.S.

Many free birthers, in fact, frequently employ cultural appropriation to exoticize birth settings and experiences (Norris-Clark often references giving birth and raising her children in the “jungles of South America”). Amanda Hess traces the phenomenon of white people using people of color as cultural scaffolding for their own birth experiences back to the mid-19th century, when the suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton publicly avowed, “‘We know that among Indians the squaws do not suffer in childbirth.’” Hess also writes about Grantly Dick-Read who wrote Childbirth Without Fear in 1942, and taught a generation of white ladies to seek birth as a sort of cultural tourism.

Dick-Read coached [the white mid century woman] in natural birth’s new performance style. He invited white women of the middle and upper classes to put on a fantasy of primitive painlessness, to wear it like a laboring gown. Natural birth was a kind of safari, and when it was over, its participants could return home to idealized and compliant family lives.

Or, as in the case of Yolande Norris-Clark, you could stay in the “jungle” of Nicaragua, and make a living off performing your wild and free white lady life in a place Norris-Clark continuously others as being “hard, brutal . . . but wild and free like no other place on earth.” Note how she uses brown bodies as backdrops for her depictions of her “jungle” home. Are you bored with your basic bitch white identity? Borrow a page from the colonialist playbook and find your truth by racialized exploitation. Joseph Conrad translated for crystal loving wellness mamas who claim they would prefer a dead baby at home than a live baby born in the “unnatural” “sterility” of the “abusive” “inverted matrix of manipulation” (a hospital).

The premise of free birth as conceived by people like Emilee Saldaya and Yolande Norris-Clark shares much in common with the premise of MAHA. Free birthers reference the history of medical violence towards [mostly white] birthing people to underscore their belief in one kind of woman and one kind of birth and one kind of baby. MAHA highlights the very real problems in the industrial food system [as experienced by mostly white people] as a way to direct MAHA-curious folks to a blueprint for one kind of “healthy” life for one kind of healthy body. There is very little room for bodies in either camp who fail to comply with these specific definitions of freedom or good health.

is the author of Invisible Labor: The Untold Story Of The Caesarian Section, and gave birth before the free birthing influencer complex (as it currently exists) was fully up and running, but still absorbed plenty of notions about the “right” way to become a parent. She acknowledges that free birthers are enticing mostly because they have valid points embedded in their exclusionary rhetoric. For example, Somerstein thinks that their emphasis on the connection between body and mind can be really useful in the birthing experience. As someone who felt as though I entered an entirely new dimension of reality during the most active parts of my labors, I agree! With my first birth in particular, I put every ounce of energy into focusing on breath and muscle release. I didn’t talk. I didn’t open my eyes. It was trippy.But Somerstein rightly points out that mindset is simply not the silver bullet free birthing influencers claim it is.

There’s a big problem with focusing too much on the right mindset as the key to achieving a ‘good’ birth: it obscures the systemic influences on birth. From the financialization of medicine, to providers’ training, to the role of racism on the environmental toxins you’re exposed to—or not—simply believing, or focusing, or buying a plan on the internet cannot overcome or negate these deeply-entrenched patterns.

Because free birthers prioritize birth in either a babbling brook or the well-lit recesses of one's own sacred domestic space, there’s not a lot of room for surgical equipment. A good birth is inherently a vaginal birth.

Embedded in these claims is that if you don’t birth in that way, you’re lacking as an authentic woman. Or that you’ve missed out on an extraordinary opportunity for self-realization. Or that you’ve set your child up for a screwed-up life. Embedded, too, is that any intervention is a disturbance of the ‘natural’ pathways of the pregnant or laboring body (and that such ‘natural’ paths are inherently good, calm, safe, gentle).

Claims that all people always have a choice about what technologies, tests, or care to accept or deny also belie reality. In theory, that’s true—you can say no to prenatal testing, or electronic fetal monitoring. And yet, there’s ample data that when Black women say ‘no’ to an intervention, they’re stigmatized, sometimes even punished; that access to midwifery is not equal; that CPS removes Black children from their families at disproportionate rates than it does from whites. [Sara here: see

’s Unfit Parent for the many ways disabled parents are also targeted by CPS]This essentialist perspective sets mothers up for disappointment and self-blame if birth doesn’t go as they expect, particularly when it veers from the ‘natural’ course. Many of the mothers I’ve spoken to about their births, both for my book and for other pieces, expressed grief—grief for the birth that they’d grown up expecting and didn’t have. Grief that if they had an unplanned cesarean, or experienced a birth injury, or if their baby experienced a birth injury, it was somehow their fault. Grief that, when it comes to the possibilities of liberation birth appears to present, they missed out.

Whenever I share any of my birth stories, I preface them by naming the many ways in which I was lucky.2 I was lucky that my pregnancies and births were relatively straightforward. I was lucky to live in a place where midwives are the norm. I was lucky to be treated as a whole person by the nurses, doctors, and midwives who cared for me. I was lucky to have supportive family members present. I was lucky to be white. To be thin. Lucky to have insurance and enough money to pay for a postpartum doula.

And part of me understands free birthers’ insistence that birth can feel empowering because my unmedicated births were empowering for me. But not every birthing person wants an unmedicated birth. Medicated births and birth interventions can also be empowering and anyway, not every birthing person even wants birth to feel empowering. In the worst cases, not every birthing person has the luxury of options when it comes to their birth experience. Not every birthing person can expect to be treated like a whole person.

Free birthers would likely use many of the statements I made above to back up their claims that hospital births are BAD full stop. But when Yolande Norris-Clark and her peers blame the entirety of birthing people’s suffering on the medical system (and feminism!!!!) and fail to consider the violence of the current administration’s attack on American families, and birthing people’s ability to control their own bodies, how convincing can their “pro-woman” argument really be? Norris-Clark, in response to whether she’d be open to more babies, said: “Yes.”

Why? Because we are, because we can, because we’re human, because children are a total blessing and the source of inspiration and love, because family is true wealth and abundance, because we defer to God’s design.

Norris-Clark’s response is perfectly in step with the conservative right’s aggressive pronatalist push, which is undergirded by the simple fact that because birthing people CAN have babies means they should. Whether they want to or not.

Modern natal care for birthing people in the U.S. could and should be a lot, lot better. But the solution to birthing inequity is the same solution to reproductive injustice. The culprit in both cases is racist misogyny, and no amount of dressing up free birth as a “gateway to consciousness” or demonization of hospital births as a “desecration of [birth’s] sacredness” will address that. In many ways, free birthers are just as noxious as misogynistic male practitioners giving women the “husband stitch.” In both cases, the individual is tasked with shouldering the burden of systemic problems. In both cases, patriarchy and the gender binary define pleasure and pain.

Did you attempt free birth at home and “fail” by needing medical intervention in the hospital? Your fault for not having the right mindset. Your fault for not doing enough research or not having enough money to shell out for Radical Birth Keeper School. Your fault for not being “woman” enough.

And, of course, there’s plenty of blame hoisted upon birthing people in hospital settings too. Did you not perform your pain well enough? Were you not white enough? Feminine-appearing enough? Thin enough? Did you not use the right tone of voice? On both ends of the birthing spectrum, the individual is tasked with creating the conditions for a “good” birth, and the individual is blamed for not correctly embodying the right sort of birthing person.

In a concluding chapter that deserves allllll the awards, Amanda Hess recounts her experience visiting a free birth retreat as research for her book. Helmed by Emilee Saldaya, The Matriarch Rising Festival took place in North Carolina, and Hess met women wearing pins declaring that “WOMAN IS NOT A FEELING,” earth-mother goddesses sucking the juice from mangos, and ultimately Saldaya herself. Hess attends a talk given by Dr. Melissa Sell (who teaches the “mindset of healing” according to her website. Sell’s methods (like Yolande Norris-Clark’s) are informed by German New Medicine, which Hess researched so we don’t have to. It’s an antisemitic theory which posits that all medical issues are caused by “conflict balls” that it's up to the individual to identify and resolve. “Speaking as the mother of a Jewish child with a cancer predisposition syndrome,” Hess writes, “This was not correct.”

As Hess listens to Sell’s talk about “pre-zero indoctrination,” she considers the disconnect between free birthing aesthetics and their most salient beliefs. “Wasn’t it odd that the internet community styled most like a hippie commune was the most bizarrely individualistic of them all? The village doctor came around to tell people that if they had a heart attack, they didn’t need to go to the hospital. They just needed to look inside themselves.”

The individual experiences birth. This is true. But every birthing person’s individual experience depends on and is informed by the collective. The collective then, is where birth reform should start. If people and institutions are trained to honor a birthing person’s individual experience, instead of preaching to the individual about how to Do Birth Right (or if they should give birth at all), we’d all have better outcomes. However that looks and whatever that means for us.

This isn’t to say that Black women, Indigenous women, LGBTQ+ folks, and other birthing people disproportionately mistreated by modern medicine aren’t organizing and empowering themselves through alternatives (or ameliorations) to hospital births. See here, here, and here! It’s just to say that the white free birthing movement largely ignores how birthing people with intersecting marginalized identities are particularly susceptible to harm and poor treatment.

These women are so enraging, because they are actually causing more harm to women. Rather than empowering all women to have better birthing experiences, it becomes a test of how worthy you are just to survive. It’s not about doing any real work but opting out of a system that you don’t like, and are hopefully lucky enough not to need. There are a lot of problems with our modern birthing system, I’ve experienced them first hand. We should advocate for better experiences for all women. I can get pregnant really easy, but I have a disorder that makes my pregnancy high-risk. It means daily injections of blood thinners or I will have a stillbirth, which I experienced before knowing I had this condition. It means even with careful medication and monitoring I can have complications like sudden severe preeclampsia that requires a lot of medical intervention to save me and the baby, which I’ve also experienced. There wasn’t really treatment or awareness of this condition even a generation ago. I’m the woman in history who had countless miscarriages and stillbirths, and likely died from pregnancy complications. I’m guessing these women don’t actually read history, or they just believe they will somehow magically avoid all that. I had two traumatic pregnancies, and two fairly (for me) uneventful ones. I was able to have mostly natural deliveries with those two, but was required to do it a hospital setting where I had to fight over and over for that right. I was quite often treated miserably by medical professionals who largely were uninterested in me having a positive birth experience, and dismissed my voice constantly. These women don’t care about other women though. I guess if you end up needing intervention then it is your own fault for however you are treated. To them it’s just all about making money by selling an idea that may or may not work out but really won’t affect them either way. My grandmother was a “good”Catholic woman who gave birth twelve times. She had no problems birthing overall. She died in her early 60’s, though, from a serious autoimmune disease. I imagine the toll all those years of pregnancy had on her body didn’t help. She barely saw the last kid out of the house before passing away.

Every time someone writes about free birth the way you did, Sara, I want to hug them and immediately buy them a drink and say thank you. And I want to do this because MY BABY AND I WOULD HAVE DIED. An educated, wealthy, white woman with relatively easy access to prenatal care with a wanted, healthy pregnancy still had to get flown across the state because of an obstetrical emergency. Women dying or coming close to it isn’t rare in America, it’s just that so few people in power give a shit. So thank you for writing so well on this topic that makes me absolutely blind with rage.