Laura Ingalls Wilder is beloved by millions for her Little House series, a fictionalized account of Wilder's childhood growing up as an American pioneer. Hers is a story of American grit that's inspired thousands of people to "return to their roots," and forge bright new futures as homesteaders.

But Wilder’s tale of hard work, individualism, and self-determination was only ever half the story. The Ingalls family never succeeded as self-reliant farmers, nor did Wilder and her husband Almanzo. While both families homesteaded and farmed in numerous locations, both also depended on government subsidies and supplemental income to survive. For the entirety of Wilder's childhood and the majority of her adulthood, she was impoverished and unsure about her future security. She was not waxing poetic about laundry.

The decidedly unsexy (and unAmerican?) truth of 19th century pioneer life is entirely missing from modern depictions of #homesteadingmamas. Tradwife content utilizes or weaponizes Wilder's pioneering narrative to disseminate ideologies of rugged individualism and insular nuclear family values. They paint a rosy picture of cozy winters spent by the fire; whimsical relationships with beloved farm animals; and most of all, an unshakeable certainty that their way of life is the best way of life.

Tradwives' rationale for this certainty rests on stories like Wilder's, stories which were instrumental in solidifying the mythology of American bootstrapping. Wilder's legacy is more powerful than the truth of her immensely difficult life. And what's more American, after all, than white-knuckling a myth even when that myth is fundamentally antithetical to the wellbeing of the country itself?

When juggernaut social media accounts like Ballerina Farm release music videos fetishizing a "simpler time" when men were cowboys and women were . . . sexy cowboys, they're relying on their followers' familiarity with not Wilder's books specifically, but the iconography of the white American dream Wilder helped create.

Laura Ingalls Wilder's most iconic book, Little House On The Prairie, opens with the following lines.

A long time ago, when all of the grandfathers and grandmothers of today were little boys and little girls or very small babies, or perhaps not even born, Pa and Ma and Mary and Laura and Baby Carrie left their little house in the Big Woods of Wisconsin. They drove away and left it lonely and empty in the clearing among the big trees, and they never saw that little house again.

They were going to the Indian country.

In the white imagination, the Indigenous characters in Wilder's books function primarily as proof of the Ingalls' perseverance in the face of hardship. They are hurdles to overcome, not fully realized characters, and they serve as background context for the primacy of the Ingalls' manifest destiny. But in order for American pioneers to exist at all, Indigenous Americans needed to be taken offstage; displaced, murdered, and systematically starved to death by the American government.

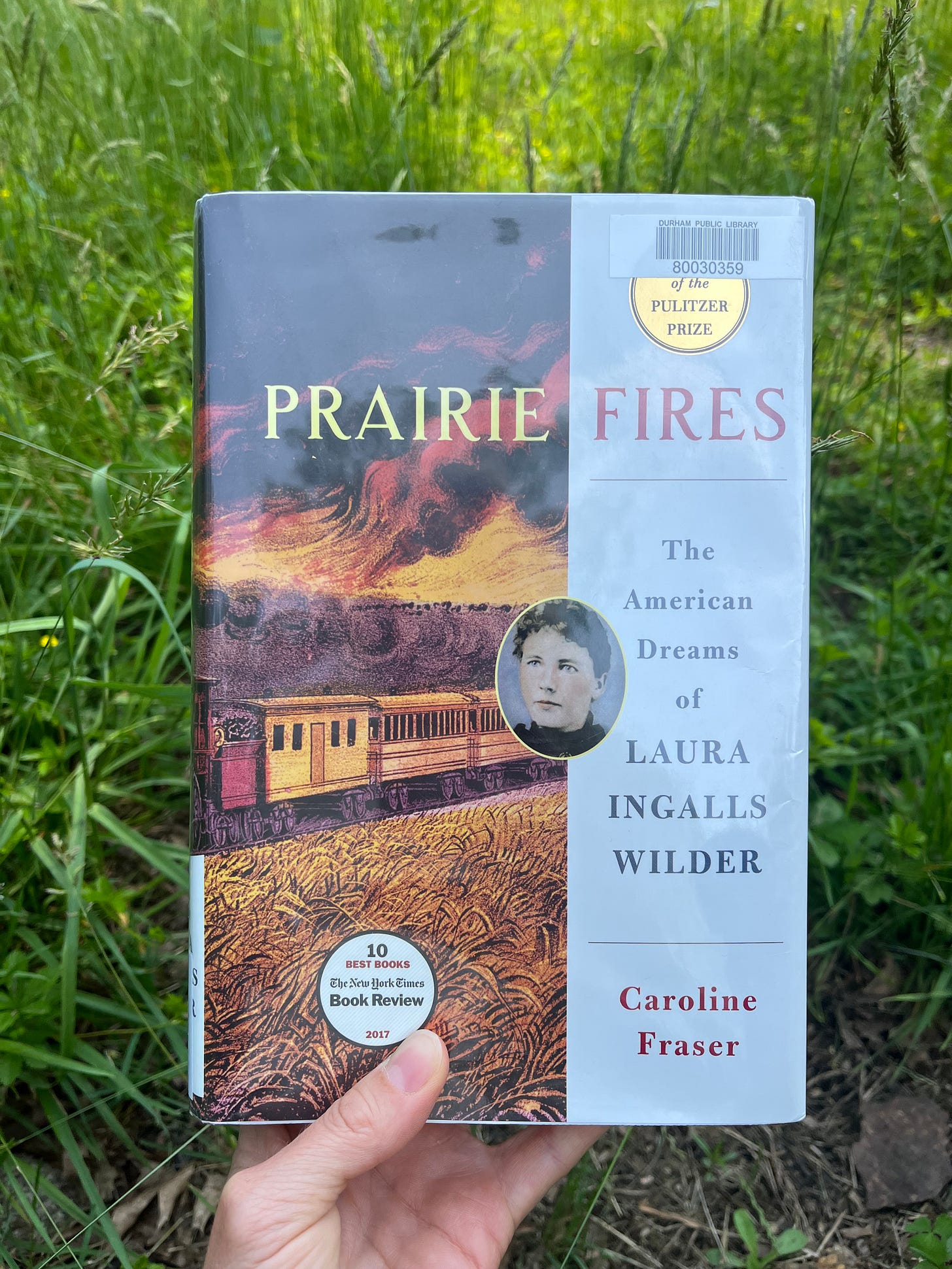

When Caroline Fraser, the author of Prairie Fires, a Pulitzer-winning biography of Wilder, was interviewed by

for her excellent podcast about the cultural impact of Wilder's books, Fraser told her that starting the book with an account of white violence towards Indigenous Americans was less a choice and more a foregone conclusion. Prairie Fires opens with an account of the U.S.- Dakota War of 1862, which killed more white Americans than the Battle of the Little Bighorn, but which had far more dire and far reaching consequences for Indigenous Americans.In Prairie Fires, Fraser writes:

As a result of the war, thousands of Indians would be driven out of Minnesota, and white settlers would permanently take their place. The Homestead Act [of 1862] gave the settlers official permission and incentive. But ultimately, it was not policy or legislation that opened the far west. It was not reasoned debate. It was wrath and righteous retribution that did it, forever changing the contour and condition of the land, pushing settlers farther west than they had ever gone before, flooding the prairies with farms, towns, fields, grain elevators, and train stations.

So much of the indelible magic of the Little House books lies in Wilder's palpable love of the Great Plains prior to white settlement. The awe she feels for the beauty of great, sweeping expanses of native flora and fauna exists uncomfortably alongside her family's homesteading goals, which contributed to the destruction of nearly everything Wilder found wild and beautiful about the unsettled midwest. The speed and breadth of white settlement led to climate catastrophes still impacting the plains today, and many of the plants and animals so beautifully evoked by Wilder are gone forever.

I emailed

to ask how her reading of Fraser's remarkable book (and her research for the Wilder podcast) has impacted her understanding of Wilder's legacy. She, like me, was a passionate Wilder fan growing up, and the Little House books were hugely formative for her.It was less about denying the framework of pioneer grit and pulling oneself up from the bootstraps -- frontier life was brutal for everyone; the grasshopper plagues alone! Can you imagine! -- then grappling with the larger power structures at play. Yes it was hard, and also, one of the largest government social programs in American history was the ethnic cleansing of the Native American population to make way for white settlers. Not to mention, the railways, which were the real force of evil in the 19th century story of American expansion.

Two things have been deeply lodged in my head since we did the podcast. One is the fact that there were something like 35 million buffalo on the plains in the 1820s and by the 1880s there were 500. That number is staggering. They had been slaughtered at the behest of the US government in an effort to remove the main food source for Native Americans as a way to starve them out. The other came from an environmental historian we spoke to, who said that he believes one of the reasons Laura's descriptions are so magical is the flora and fauna she's describing no longer exist. She captured, from memory, a world we've made extinct.

Regarding the locusts, which Wilder fans might remember as wiping out Pa's wheat crops (and nearly everything else), the reality was almost unbelievably horrific. Fraser shares a contemporary meteorologist's accounting of the 1875 grasshopper swarm, which "appeared to be 110 miles wide, 1,800 miles long, and a quarter to a half mile in depth . . . they covered 198,000 square miles, an area equal to the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont combined . . . the cloud consisted of some 3.5 trillion insects."

I MEAN.

The "way back when" fantasy being sold by tradwives online never reckons with the violence and genocide that paved the path for white settlers to pursue their American dream; their magical memory-making of "the good old days" rewrites American pioneer life as peaceful, uncomplicated, and rewarding. Full stop. We don't hear about side jobs, crop failure, environmental disasters, or mind-numbing exhaustion.

And the nostalgic evocation of the American Pioneer is so cemented in the mythology of the country that it's disarmingly easy for it to not only exist relatively unchallenged online but influence thousands of young people disenchanted with the choices they've been given in modern life.

Let's take motherhenhomestead, for example. In this reel, we see a young woman modeling a sexy little milkmaid (raw? WHO CAN TELL) dress amidst a few picturesque chickens. We see a twee porcelain bowl full of artfully arranged berries. We see white sheets drying in the breeze, cows walking across a paved road, a man kissing a woman in the middle of a corn field. “I’m going for that little house on the prairie kind of summer.”

Pioneers like the Wilders had no time to adorably make out in the middle of chores, which were never ending. This milkmaid dress would be covered in dirt and animal shit within minutes of the wearer engaging in any real farmwork. And the berries in the bowl are seasonally inconsistent! Strawberries grow in the spring, blackberries in the late summer, but WHO CARES about such such things when everything looks SO PRETTY.

One of the big draws of homesteading trad content is the ability to be self-sustaining, to never have to rely on the government or social safety nets for survival. See gubbahomestead, who hearkens back to the "inspiring" canning and preserving work of American great grandmothers to ensure their families were reliably fed.

But white settlers trying to create profitable farms on the prairies were rarely (if ever) self reliant. They were rarely well fed! The vast majority of successful farms created in the wake of the Homestead Act were the earliest version of today's factory farms, massive operations called "bonanza farms." Bonanza farms were created in the late 1870s by wealthy businessmen who held bonds in the Northern Pacific Railway. When the Northern Pacific went under, these men used their bonds to purchase massive tracts of land. They had the capital to invest in technology, equipment, and workers, and the railroads used the example of bonanza farms to lure would-be homesteaders further and further west, even though the average farmer would never be able to compete with bonanza farmers.

The Ingalls, and thousands of other homesteaders like them, regularly relied on government assistance for survival. The entire reason for them being in the American West in the first place – the Homestead Act – was itself, according to Fraser, "one of the largest federal handouts in American history."

And, as Fraser writes, the ability for farmers to survive solely on farming hasn't changed much since. “In 2015, median farm income was negative 765 dollars. Ninety one percent of farmers are dependent on multiple sources of 'off farm' income, just as Laura Ingalls Wilder was, and her father before her.” In 2023, the median farm income was negative $900.00. Ballerina Farm is the bonanza farm of the modern age. Even though farming has become more economically precarious, not less, the story being sold by the Neelemans is just so darn attractive. Never mind the generational wealth and privilege that enabled them to "build a business from scratch." If they can do it, and if they can make it look so beautiful, then surely you can too!

Speaking of modern day bonanza farmers! Ree Drummond AKA The Pioneer Woman AKA the momfluencer who paved the path for Ballerina Farm and all aspiring Ballerina Farms, had made millions on the American belief in Good And Simple white pioneer ladies. She sells her followers recipes for baked beans and mashed potatoes from her cozy kitchen, which sits on "an estimated 9% of Osage County land that was once in the hands of the Osage tribe. The land’s estimated worth is $275 million." Drummond's net worth is somewhere in the ballpark of 50 million, NOT counting any income generated from the dubiously acquired land. Despite this, she continues to profit from her performative identity as a hardscrabble pioneer wife. I think this has less to do with the quality of her performance and more to do with white Americans' desire to believe in a version of history that makes them feel most comfortable.

Laura Ingalls Wilder was a fierce Libertarian in the last half her life. Her absolute CHARACTER of a daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, in fact, is known as one of the "three mothers" of Libertarianism, along with Isabel Patterson, and Ayn Rand.

In a letter to a friend, Wilder wrote:

Now here we are at 78 and 88 . . . paying taxes for the support of dependent children, so their parents need not work at anything else; for old age pensions to take care of those parents when the children are grown, thus relieving the children of any responsibility and all of them from any incentive to help themselves.

The older Wilder got, the more the idea of collectivism seemed to disgust her. Her turn towards Libertarianism has been credited for the incongruous and aggressively individualistic Fourth of July speech in Little Town On the Prairie, largely believed to have been added by Lane, who edited much of her mother's work. Such an unflinching commitment to individualism at all costs feels so inconsistent for a person who grew up not only relying on community and government assistance for survival, but also grew up knowing the pain of extreme poverty.

Prior to adopting Libertarian politics, Wilder worked (and borrowed from) the Federal Farm Loan Program for several years, making this about face all the more hard to make sense of. Fraser posits that Wilder's uncompromising stance was born from deep shame and the unresolved trauma of growing up dependent on the kindness of strangers (and systems of power).

As she knew too well, people who are poor are ashamed. It's easier to blame the government than to blame yourself. Wrestling with shame was one of the reasons she wrote her books–Nellie Oleson was the devil she put behind her–but she also labored to lift that feeling out of her stories and out of her past, setting aside her father's debts and her own grubby days working for the Masterses. She said she made the changes for children, but she did it for herself too.

In the Ballerina Farm post that takes up the VAST MAJORITY of BF real estate in my brain, Hannah Neeleman explicitly calls upon her pioneering ancestors as a way to both romanticize and morally uphold her own lifestyle. Like the champion farm wives of yesteryear, I strive to be a good homemaker. Women like Neeleman are simply reciting a script that was written (in part) by people like Wilder, people anxious to make sense of their own difficult lives. At the very beginning of her writing career, Wilder gave a speech entitled "The Small Farm Home," at the Missouri Homemakers Conference in 1911, the content of which would become characteristic of her earliest professional writing.

There is a movement in the United States today, wide-spread and very far reaching its consequences. People are seeking after a freer, healthier, happier life. They are tired of the noise and dirt, bad air and crowds of the cities, and are turning longing eyes towards the green slopes, wooded hills, pure running water and health-giving breezes of the country.

This could be a voiceover on a tradwife/Maha reel.

Wilder goes on to offer a guidebook for how to create a self-sustaining farm, conveniently leaving out the part where she ever actually managed to do that. But such was the power of maybe her shame and her desire to crystallize the American dream of self-reliance that she offered these partial truths to anyone who would listen.

Wilder's internalized shame seems to have impacted many others who tried and failed to make their homesteading dreams come true, particularly if they grew up in the earliest days of American western settlement. When Roosevelt put several New Deal plans into effect following the Great Depression, he made a speech about the perils of isolationist self-reliance, and the thousands of destitute farmers "who had nothing left but the dreams of their homesteading ancestors" hated him for it.

Wilder's books (as much as I love them!) have been instruments of American propaganda since way before today's tradwife weaponized them to endorse traditional gender roles, the "toxicity" of birth control, and "complementarianism." During the reconstruction of Japan following World War II, the American military had Wilder's books translated and distributed amongst millions of displaced Japanese citizens, many of whom were starving. The cynicism of a country weaponizing the myth of American individualism in order to sell American democracy to a country they've decimated is almost stunning.

The pain and insecurity of our current political moment has A LOT do with Americans' belief in the myth of the American Pioneer. But it's always been just that: a myth. White settlers on the Great Plains worked hard. They persevered, and they lived through unimaginable hardships. But, as Caroline Fraser's Prairie Fires so clearly shows, it was not a particularly beautiful story, and our cultural amnesia has only wrought more and more ugliness.

Critical or adoring scholars and readers might agree about one thing: the Little House books are not history. They are not, as Wilder and her daughter had claimed, true in every particular. Yet the truth about our history is in them. The truth about settlement, about homesteading, about farming is there, if we look for it–embedded in the novels' conflicted, nostalgic portrayal of transient joys and satisfactions, their astonishing feats of survival and jarring acts of dispossession, their deep yearning for security. Anyone who would ask where we came from, and why, must reckon with them.

Eerie how many parts of the Prairie Fires descriptions could perfectly describe the situation in Palestine today (government propping up settlers, using starvation as a tool for genocide, etc...). White supremacy and colonialism are alive and well!!!

Thanks for highlighting this great book and making so many connections to influencers today. I've been a lifelong LIW fan and Prairie Fires really helped me start to unpack some of the myths I had instinctively bought into!

And that’s even without mentioning: Mary becoming blind, due complications of scarlet fever (I.e. what can follow a strep infection without antibiotics). Ma & Pa losing their baby son traumatically due to illness, and Laura later traumatically losing her baby son (possibly due to a seizure, but who knows.) Laura’s husband becoming permanently disabled due to diphtheria (now there’s a vaccine) as well as one or both of them possibly becoming infertile (they believed) since they were unable to have more children afterward. Under such circumstances, I can’t imagine being beautifully “in the moment” with my children vs. constantly worried. But sure, let’s drink raw milk and forget about vaccines…