When you are a woman who writes about other women from a culturally critical lens, you will assuredly be accused of the following:

Jealousy

Bad feminism

Pettiness

Focusing on the “wrong thing”

Tearing other women down

GOSSIP

As right-wing magazines like Evie gain mainstream traction, a writer positing that maybe choice feminism (for example) isn’t the BEST way to assess whether or not a society is built on a foundation of misogyny and sexism, is in danger of being written off as little more than a frivolous gossip with too much time on their hands. The case of Megan Agnew is instructive. When she wrote about Ballerina Farm, the article was immediately met with a slew of comments accusing Agnew of forwarding her personal [feminist] agenda by writing a “hit piece” about Hannah and Daniel Neeleman.

And yes, of course, a writer can frame a subject’s quotes to create a narrative and to put forth a certain thesis. Maybe Agnew could’ve simply not included Daniel’s haunting comment about Hannah being bedridden for days at a time due to exhaustion. Maybe she could’ve referred to Daniel as “passionate” re his ceaseless desire to show Agnew his various ditches. Maybe she could’ve labeled his constant presence as “loving” and “committed.” But all of these editorial decisions would also betray a lack of pure objectivity, the very thing trad apologists claim to want from journalists who cover tradwives.

The very notion of journalistic objectivity is a fallacy. Human beings are not capable of approaching anything with unadulterated objectivity, because we are people with histories and lived experiences that necessarily impact our understanding of the world. When a reader bases their critiques of a writer’s work on that writer’s subjectivity, I think it sometimes says more about the reader’s subjectivity than anything else.

But back to gossip. Gossip has always been weaponized by and against marginalized groups. It’s been linked to gender in attempts to weaken its potential for disruption. It’s been maligned time and time again as a useless and frivolous activity enjoyed by silly people with silly thoughts. This is all by design of course, because when marginalized groups talk to each other, when they share stories and information, they pose a real threat to the hegemonic status quo.

Which is why the folks who want to make sure the people in charge stay in charge have always belittled the gravity of someone’s argument (or story, or personal experience, or opinion) by reducing that person’s words to gossip. In this upside down logic, gossip and personal perspective are one in the same, so if a person’s identity or personal experience impacts their understanding of a situation, the narrativization of that understanding becomes immediately suspicious. It doesn’t take longer than a few seconds to determine that such a metric is ridiculous. All beliefs stem from the personal, which is why, of course, the personal is political.

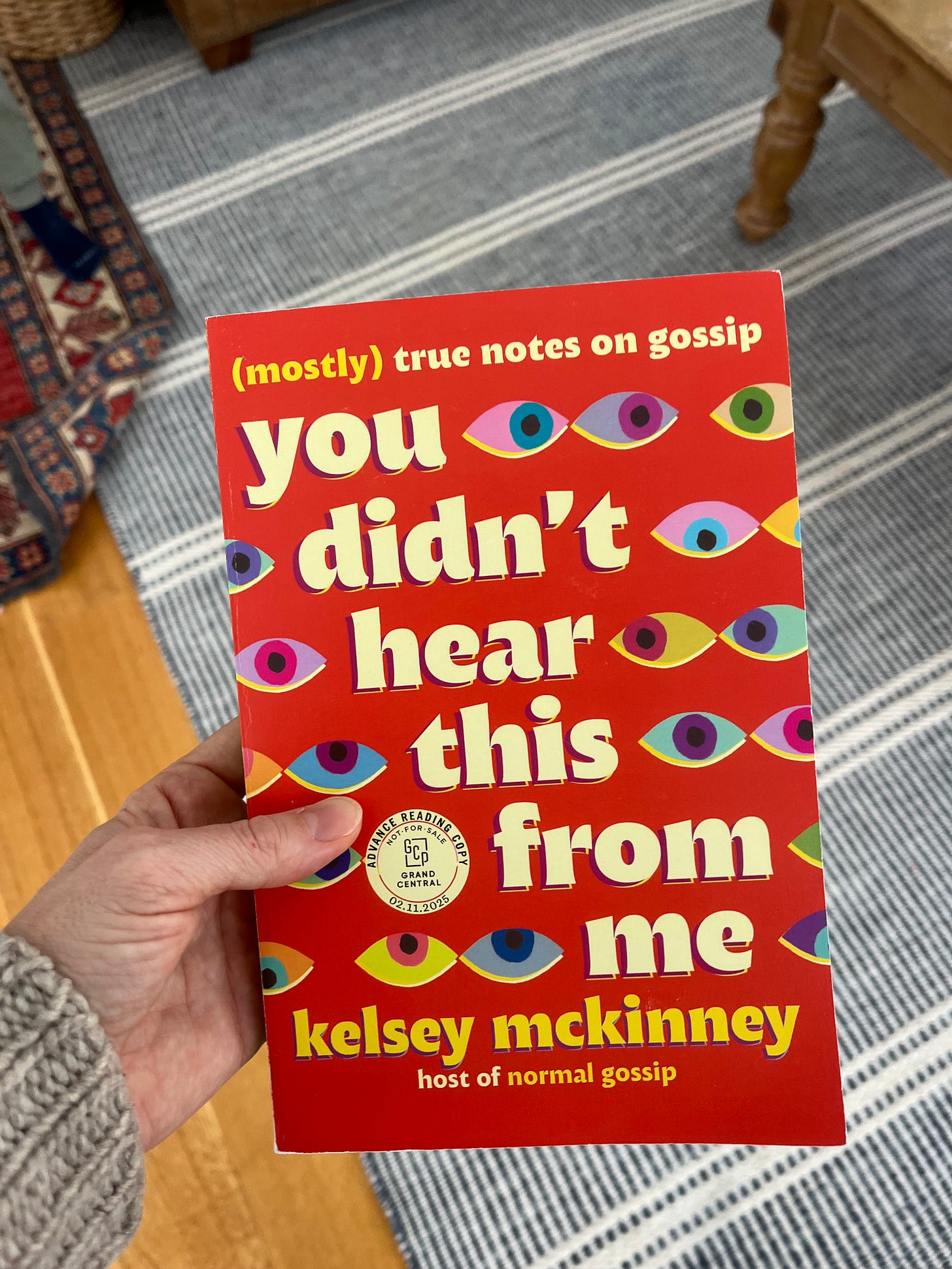

Kelsey McKinney is the former host and dowager queen of the impossibly delicious podcast, Normal Gossip. If you haven’t yet listened, you are IN FOR A TREAT and I am jealous of you! I can’t think of a single podcast that provides more unadulterated joy and fun than Normal Gossip. McKinney is also the author of the equally delicious new book, You Didn’t Hear This From Me: (Mostly) True Notes On Gossip. In her book (which I devoured within a 48 hour period), McKinney writes:

To gossip well and to tell a story well, the teller must occupy a real presence in space and time and tell the story from there, as a combination of their experience . . . What is essential, then, to weaving a good story of any kind (gossip or not) is to have an identity and a point of view from which to tell that story. All writing is about the journey from information to telling, not just the final product. You cannot observe the world without eyes to see it through.

It’s indisputable that the best gossip is narratively sparkly - it involves details, specificity, and effective dramatic structure. And the criteria for good gossip is inextricably linked to the gossiper’s personhood and her ability to sort through a set of information in order to make meaning. Mrs. Arkansas’s personal history will make her tell a very different story about Hannah Neeleman’s winning Mrs. America speech about motherhood than I would. But I would also tell a different story about that speech than another feminist writer would. It’s not just an individual's politics that impact a person’s delivery of information; it’s the individual’s entire history.

McKinney’s point that all writing (gossip or not) is born from a person’s subjectivity is not, to me, a radical one. It is simply a self-evident truth. And yet, this truth does little to combat the negative power of labeling something as gossip. Particularly when the purveyor of that gossip (or essay) is a woman.

When a man writes critically about another man’s political or cultural significance, he is simply a man with an opinion. He is rarely accused of moral bankruptcy or envy or emotionality blinding his critical vision. But when a woman writes critically about another woman’s political or cultural significance, she must have an ulterior motive.

The particularity of the misogyny at play here is interesting to me, because it reveals so much about the ways in which gender has been constructed to disempower some and empower others. The male cultural critic is not expected to be a blank slate; his life experience is integral to the value of his cultural criticism. He is expected to have specific values and to have a clear code of ethics through which he processes information.

But the woman endeavoring to provide cultural analyses through the lens of another woman’s celebrity, for example, is not to be trusted for the very same reasons the male cultural critic is deemed trustworthy.

Is she a mother? She can’t possibly speak with any authority about a woman who is not a mother. She also can’t possibly speak with any authority about a fellow mother since no two experiences of motherhood are identical. Maybe she struggled with infertility and conceived via IVF, which would, of course, discredit her from writing about a fellow mother who conceived her children without medical intervention. Does she do waged work? She can’t write about women who do unwaged domestic and caregiving work. And it should go without saying that a mother whose work is centered in the home better not have an opinion on the term “working mom.”

Is she a woman without children? She can’t possibly speak with any authority about a mother. She doesn’t understand maternal struggles since she doesn’t share them, so she should really stay in her lane and not have an opinion about the ways in which the idealization of motherhood makes life for non-mothers more complicated and difficult. She is probably jealous. She is probably bitter. She can’t possibly speak about a fellow childfree woman either, because she’s biased you see. She has an agenda.

Is she single? Is she a woman of color? Is she queer? Is she disabled? Is she trans? She’s not impartial, she’s not objective, she’s too close to the situation, she’s too emotional, she’s holding a grudge, she’s basing her claims on nothing but GOSSIP.

Sexism, misogyny, and white supremacy are responsible for women’s storytelling (gossip or journalism!) being denigrated as fundamentally suspect. It’s easy to judge a woman’s writing based on her human weaknesses (by which I mean the fact that she is a person in the world) because a woman’s identity is so much more politicized than a man’s identity. Her status as a mother (or not) is politicized. Her body is politicized. Her beauty is politicized. Her job is politicized. Her diet is politicized!

And of course, women are only one of many groups whose marginalized identities mark them as unreliable narrators of whatever story they’re trying to tell. Even if that story is their own.

When I was conducting interviews for Momfluenced, many Black momfluencers told me they struggled to land specific brand partnerships because they weren’t viewed as “universally marketable” across the motherhood demographic. In this case, apparently race precludes one from writing sponsored content about paper towels, diaper bags, and baby food blenders. On the Maintenance Phase podcast, Aubrey Gordon has shared her anxiety that her status as a fat woman will (unfairly!) weaken her arguments about medical and societal anti-fatness. Trans people are famously not trusted to make decisions about their own bodies, nor are their stories prioritized in the media’s assessment of gender-affirming healthcare. In all of these cases, a person’s lived experience is utilized to discredit their words and the way they make meaning. A straight white man’s personal history, on the other hand, is frequently held up as proof positive that his op-ed or legislation or fucking Presidency or gossip is worth heeding.

It makes sense to me that women are not only more frequently accused of gossip but more likely to engage in storytelling (gossip) because it’s one of the best ways for us to make meaning of our own identities. The more one’s identity is used as a political and social bargaining chip, the more urgent becomes the project of making sense of our own lives. In You Didn’t Hear This From Me, Kelsey McKinney writes:

“Strong minds discuss ideas, average minds discuss events, weak minds discuss people,” Socrates or Eleanor Roosevelt or whoever said. But the ancient Greeks also said that all philosophical commandments can be reduced to a simple goal: “Know yourself.” And what I said, about myself at least, is that gossip isn’t a tool so much as it is a reflection. The way we gossip, who we gossip about, and how we respond to these stories show us the person we are. They help us understand where we fit in the greater scheme of trying to be a person in the world. The truth we are searching so desperately for is self-knowledge.

Sometimes, as an attempt to preemptively prevent emails and DMs about my work being too gossipy, I will explicitly label a piece as gossipy. When I do this, I’m not denigrating my own work. I’m simply recognizing that things like a quippy, sometimes profane tone; a sense of unabashed writerly fun; and subject matter involving women’s choices will inevitably be used as a way to diminish the value of my work. I don’t believe that two gals having a blast analyzing the stunning absurdity of a magazine profile makes their analysis of the conservative right worthless. I don’t think a giddy sense of fun vis à vis prairie chic clothing brands invalidates what is fundamentally a conversation about celebrity, monarchy, media narratives, and the performance of femininity. And sorry, but I’m cool with talking shit about beautifully packaged colostrum protein powder if I’m also interrogating gender, diet culture, and the influencer economy!

This isn’t to say that my writing is above reproach. This isn’t to say that all of my writing is even good. This certainly isn’t to say that I’ve never fucked up in my writing! I have! Many times! But I resent (and feel so exhausted by) the fact that I feel such pressure to protect my credibility with the “right” kind of language; a constant acknowledgement that of course my opinion is but one mere woman’s opinion; and frequent self-disparagement. I resent the fact that I have to waste my time worrying about whether or not my earnest-as-fuck sentiments will be defanged with the label of gossip. Women don’t require ulterior motives to care about the world and their place in it.

I adore the Normal Gossip podcast, and I adored You Didn’t Hear This From Me, because I adore thinking about the human experience. I write about topics that trigger my strong personal emotional response because that means I care about those topics. And when I frame my cultural analysis on a case study of a particular woman, it’s because I think people are more interesting and more illuminating than abstracts. Thinking about the ways in which other people live is one of the best ways I know of making meaning. Not only of my own personhood, but of the seas in which I’m swimming. So cheers to gossip. All hail being too emotionally involved. And fuck yes to subjectivity.

And now - for a little bit o’ FUN: I would love to ask the question asked of every Normal Gossip guest here: What’s your relationship to gossip? I’ll tell you mine (in the comments) if you tell me yours! Maybe I’ll also tell you what I really thought about Hannah Neeleman’s Mrs. America speech 👀👀👀

Slightly off topic but all I am thinking about now is how different the response to the Ballerina article would have been if they merely attached a male name as the author. I'm sure much research has been done on this, I may have found a rabbit hole to go down today. Also, have you already discussed how pastors focused so much on gossip being a sin because it kept women from warning each other about the ahem, bad behavior of the men in the church? I can't remember which substack or book discussed that.

When I think of gossip in my life, my mind immediately goes to work gossip. When you are not one of the decision-makers who have an outsized impact of the experience of something that is unfortunately so often a very dominant part of people's lives, gossip becomes not just sense-making for opaque decisions, but also a way to find your people and as many have pointed out below communicate about the people to watch out for in a workplace.

Also, it's just so satisfying to get the tea on a shitty former workplace.