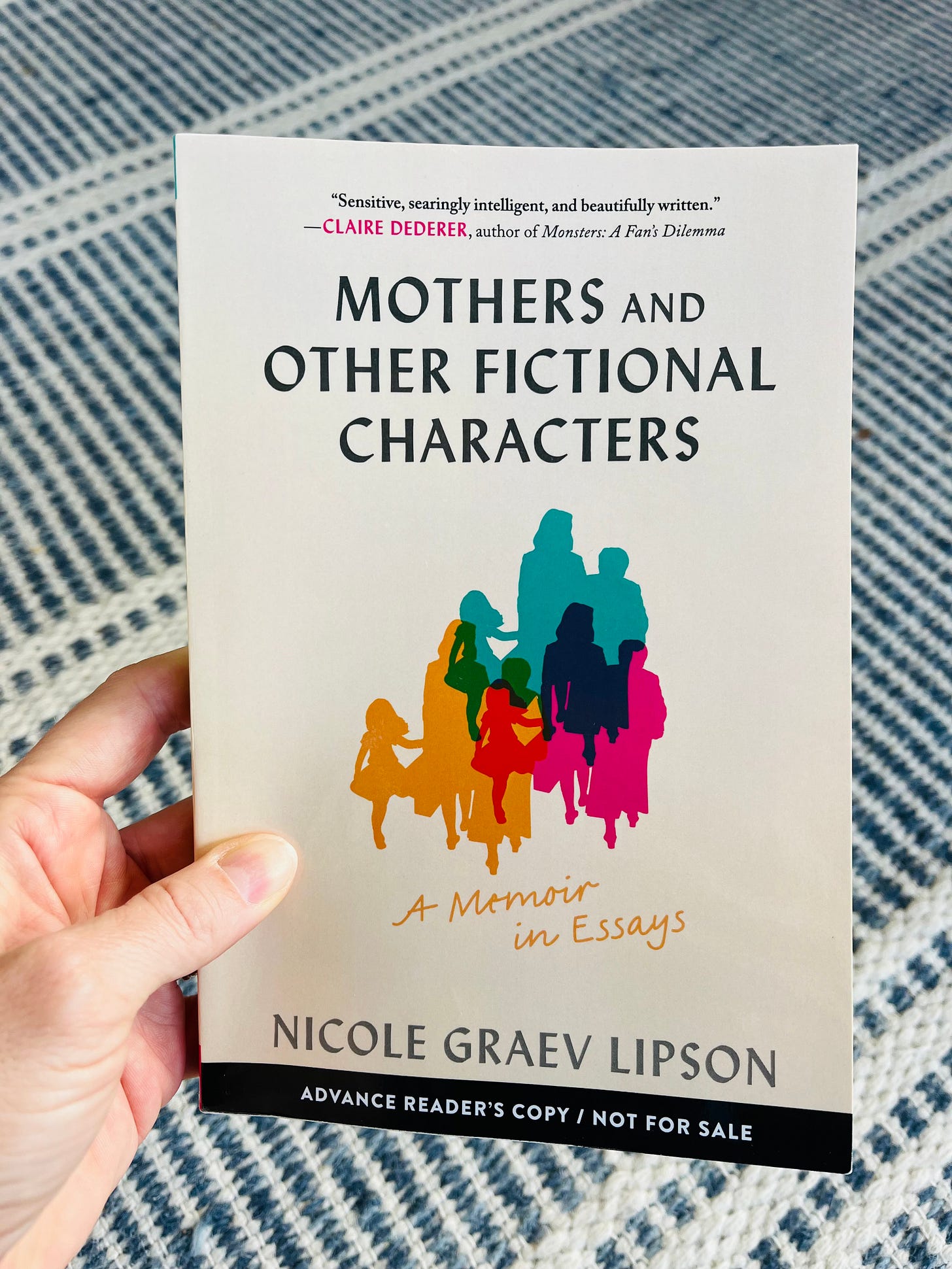

In her new book, Mother And Other Fictional Creatures: A Memoir In Essays, Nicole Graev Lipson writes this:

There’s a risk I take in writing this essay, a question skulking under its belly like a shadow on the sea floor, and that question is this: “If you yearn so deeply for solitude, is it possible you shouldn’t have had children?” I have asked myself this very question at times, and the asking has been like a riptide through my blood.

But slowly, I’ve come to appreciate this question, as one appreciates useful things, because I see how perfectly it encapsulates the central problem of motherhood as an institution, which is its failure of nuance, its relentless oversimplification, its devotion to binary. Either you adore your children or you do not; either you enjoy motherhing or you do not; either you were meant to be a mother or you clearly, decidedly–monstrously–were not.

Mothers And Other Fictional Characters is a book that resists categorization, much like the experience of motherhood itself. In essays that explore everything from the role of female soulmates in women’s lives to the fraught desire to be seen as a MILF to the complicated question of what to do with frozen embryos when you are done having children, Nicole Grave Lipson plumbs the depths of what it is to be human. It’s a motherhood book, sure. But what does that even mean? And what can the existence of the category “mom book” elucidate about the role of motherhood in American culture? By interrogating the various ways the role of mother is embodied, manipulated, and utilized, Nicole shows the reader again and again that The Mother is a role moms must learn how to play. And while this role can be stifling at times, it can also be shed and remade and repurposed as many times as we want. As many times as we need to in order to be ourselves.

Sara: One of the reasons I love your book so much is because it is about motherhood SURE but mostly it’s about being human. This is a silly thing to say because motherhood is always about being human. But I guess I was struck by your freedom to pursue narrative threads that didn’t necessarily neatly fit into the “mom book” package. This is a set up for MULTIPLE questions, but first, what does the phrase “mom book” bring up for you?

Nicole: As soon as I hear the word “mom book,” I can’t help but think of mom jeans, mom brain, mom blog—all the compound terms that manage, with those three little letters, to instantly make anything trivial and unstylish and lightweight. To me, the problem with this term is how reductive it is, how instantly it flattens whatever book it’s describing into a single, one-dimensional category, with no room for complexity or nuance. And the “mom book” label feels uncomfortably similar to the way the identity of “Mother” (with a capital M) tends to eclipse all other aspects of a woman’s personhood after she has children--the fullness of her being reduced to this single role. The receptionist at my kids’ dentist insists on addressing me as “Mom,” no matter how many times I’ve said to her, “Please call me Nicole!”

My book, like so many that might be labeled as “mom books” (including yours, which changed my life)—grapples with themes that have intrigued human beings for time immemorial: desire, infidelity, beauty, marriage, friendship, aging, love, mortality. These are hardly topics relevant only to “moms.”

I think the biggest tragedy of the “mom book” category is the disservice it does to men and other non-mother readers, by suggesting that there’s nothing of value in these books for them. Interestingly, some of the most passionate and supportive early readers of Mothers and Other Fictional Characters in my MFA program were men. Would these same male readers be finding my book now if they’d never encountered it as a syllabus requirement? Sadly, I’m skeptical. Once a book gets that “mom book” label, I think it’s hard for it to reach other sorts of readers.

Anyway! I’m so happy that you see Mothers and Other Fictional Characters as an exploration of being human, because that’s really how it felt to me in the writing. Womanhood and motherhood are central to the story—but only insofar as these experiences are part of the human condition, not separate from it. The beautiful memoirist Kelly McMasters described my book as an exploration of “existing as a multidimensional woman in a binary world.” I love this description so much. And I’ll add that the world doesn’t make it easy for women to exist in many dimensions—it’s weirdly hell-bent on reducing us to stock characters.

Sara: I’d love to hear about your publishing journey for this book - it feels like it might have been hard to pitch only because it isn’t about highly specific aspects of motherhood. I ask this as someone who tried and failed to sell 2 other “mom books” prior to Momfluenced! Neither of these books obeyed the rules of a tight elevator pitch, and I’m sure they didn’t sell for a variety of reasons, but their discursiveness was definitely part of it. Lack of focus can obviously be a bad thing in writing, but strict focus can also feel a bit restrictive, right? Wondering about how you thought about this balance.

Nicole: The “elevator pitch” is the bane of my existence.

Whenever I sit down to write, it’s always some sort of confusion that brings me to the page. In many ways, Mothers and Other Fictional Characters is about the state of being ambivalent or of two minds about things: I write about what it was like to find myself achingly attracted to a younger man in the midstream of an otherwise happy marriage; about my deep uncertainty about what to do with my frozen embryos left over from a successful round of IVF; about wanting to raise a feminist son but also…feeling oddly proud when my mother proclaimed him “macho” at eighteen months, as he paraded around the house in his diaper banging on things? I’m fascinated by our inner contradictions as humans, the many layers and multitudes we contain—and I’m fascinated above all by how we can intellectually grasp all the terrible ways our culture tries to bend us to its will, while also…knowingly bending to its will. This is all to say that, not only does my book not lend itself to a tidy summary, but in many ways, pushing past tidy summaries is its entire point!

It took a while for my agent and I to find the right editor for this book, and this absolutely had to do, in part, with the fact that the content can’t really be boiled down to a single, splashy argument. Several of the editors who passed on the book basically said as much—and one in particular noted that while it was precisely the kind of book she devours as a reader, she didn’t see a clear way to package and publish it.

I completely agree with you about the beauty of finding a balance between discursiveness and focus. When I began writing this book, I didn’t actually know I was writing a book! The first few essays in it were all originally written as standalone pieces, which I submitted and published individually in literary journals. But after about three of these, it dawned on me that while on the surface they were about quite different things--the affair my mother had when I was in high school, for example, or the tyranny of female beauty standards—they were all circling in their own way around the same theme: the blurry line between truth and fiction in women’s lives. I’d like to think that the book has an internal logic and pattern that holds it together, despite the many detours it takes.

Sara: Your essay about unused (feels like a callous word!) frozen embryos was such a sensitive interplay between the science of human life and the emotional experience of being the one to bring about human life. It never fails to knock me over that in some cases (not all, of course), human life comes about because another human decides they want that life to come about and takes the appropriate action to make it happen. It’s a rather awesome weight.

Nicole: Just hearing you say this makes me want to pull my children close and apologize for all the ways I’ve failed to keep in mind that I longed desperately to bring them here. What you say is so true, and yet in the day-to-day as a mother I often lose sight of the monumental miracle that is creating new life, and the tremendous privilege it is to get to tend to that life. I get caught up in the weeds of figuring out what’s for dinner and whose carpool turn it is and trying to locate an orange shirt before school Spirit Day.

There are many reasons why I resent the mental load of motherhood and the millions of minutiae we’re taxed with keeping track of every day—but for me this is the most painful of all of them, how it hijacks our attention away from the most profound and meaningful aspects of raising children.

Sara: Talk to me about platonic love! Your essay about one of the loves of your life (your dear friend) might’ve been my favorite.

Nicole: It makes me so happy to hear that you enjoyed “The Friendship Plot. It’s one of the essays I most enjoyed writing, because while many of the others were set in motion by discomfort or uncertainty or fear, this one was set in motion by gratitude.

What I try to illuminate in that piece are the ways that female friendship can play just as central a role in a woman’s life as long-term romantic partnership, and I use my relationship with my friend Sara as a sort of case study to get at this. In popular culture and literature, female friendship often serves as an emotional training ground for what’s supposed to be the most central relationship in a woman’s life: her relationship with her husband. In the traditional “marriage plot” narrative, the intimacies of girlhood friendship get left behind at the altar. Another prevailing narrative about female friendship is that women are wired for rivalry, and that our relationships are therefore fundamentally toxic and not to be trusted. Both of these storylines serve the same purpose, I think, which is to stoke the ego of the patriarchy.

A therapist friend once shared with me that many of her straight, married women clients have admitted to her, “somewhat sheepishly,” that while they love their husbands—of course, of course, blah blah blah!--it is actually their female friends with whom they are most emotionally intimate. I found this word “sheepishly” really interesting and illuminating. Why should the beautiful depth and power of female friendship be made to feel like a dirty secret? I wrote that essay as a sort of protest against this sheepishness—as a way of saying, I love my dearest friend as well as my husband. Both/and. Not only do these two truths not cancel each other out, but together, they’re what make me whole.

Sara: I’m suddenly remembering a class I took in my first year of grad school in which we read an academic article about how friendship was the primary romantic focus of Victorian women’s lives. This had a lot to do with the fact that marriage was still mostly viewed as a business arrangement, and the gendered spheres were so separate, but it was really illuminating. There’s a freedom in intimacy that exists outside of systems of social organization.

Nicole: I couldn’t agree more. In the book I investigate what makes the love between me and my closest women friends feel so very different from the love between me and my husband, or my love for my children. This platonic love isn’t better, exactly--I hesitate to say better. But I do think that in many ways it’s less restrictive and perhaps purer because it is so free from obligation. My husband and I chose to commit to each other, and we love each other deeply. But I’m not sure the love between two married people can ever fully wrest itself free from its contractual origins—there’s a sort of constant underlying awareness that one must pull their weight and hold up their end of the bargain, and therefore a constant desire not to fall short. And while I love my children with every inch of my being and have spent hours of my life wishing I could literally ingest them, parental love always carries the formidable weight of duty.

Friendship, on the other hand, has very few scripted requirements or transactional terms. It’s a completely voluntary dance between two humans bound by nothing at all but their mutual desire to be there for one another in life. Every act of friendship is an active choice, made freely. I think this retreat from obligation is what makes female friendship unique and special. Being a woman can feel like a constant, white-knuckled attempt to live up to other people’s expectations, but with our closest female friends, we can simply be. That escape can feel so delicious. For me it feels deeply vital.

Sara: Can we talk about the concept of the MILF? A few years ago, I wrote about wanting to be a “hot mom” for Glamour, and I think so much of this has to do with women’s desires to retain their identities outside of motherhood. It’s rather disorienting to be trained to view your physical appearance as being integral to your sexual (and social!) desirability only to be told in so many quiet and loud ways that you’re no longer an independent actor in the world of sexual attraction once you have a child. On the one hand, my desire to “be hot” can be framed as a rejection of the invisibilizing force that is motherhood, but on the other hand, it’s just beauty culture and diet culture wrapped up in different packaging. It’s complicated! What do you think?

Nicole: I love that you wrote about this, too. The “hot mom” aspiration is real.

While writing Mothers and Other Fictional Characters, I was interested in critiquing the reductive narratives imposed on women, yes. But I was even more interested in exploring the ways we can become complicit in constructing these narratives against our better judgment. I’m not sure there’s any realm of female existence where this phenomenon—of behaving in ways that run counter to our values and conscience--is more apparent than in the realm of beauty and physical appearance.

Do I or most women I know want to spend hours of our one and only precious life plucking our eyebrows or dyeing our hair or counting the number of carbs in a Clif bar? We do not. We understand that there are far more meaningful things we could be doing with our time. And yet….here we find ourselves again, plucking and dyeing and counting. From a purely intellectual standpoint, I categorically object to the term MILF, and the way it essentially gives carte blanche to barely pubescent boys to assess and evaluate the bodies of grown women. I could provide a lengthy feminist analysis of this term—and in the book, I do! But in the end, all this intellectual clarity is no match for the infinite ways I’ve been trained since girlhood to measure my worth according to others’ approval, and to confuse being desired by others with my own desire.

When I hit forty, I did find myself weirdly longing to become a MILF, because I understood it to be the last bastion of female desirability available to me as a woman whose fertile years were numbered. I think my own desire to be a MILF was less about wanting to retain an identity outside of motherhood and more about wanting assurance that I was still vital and alive, that my life still held mystery and zest and promise. In some strange unconscious logic, I’d determined that if I was still sexually desirable, this would mean I still had it going on inside. But this of course makes no sense whatsoever. Having someone want to fuck you doesn’t charge your life with meaning. Living does.

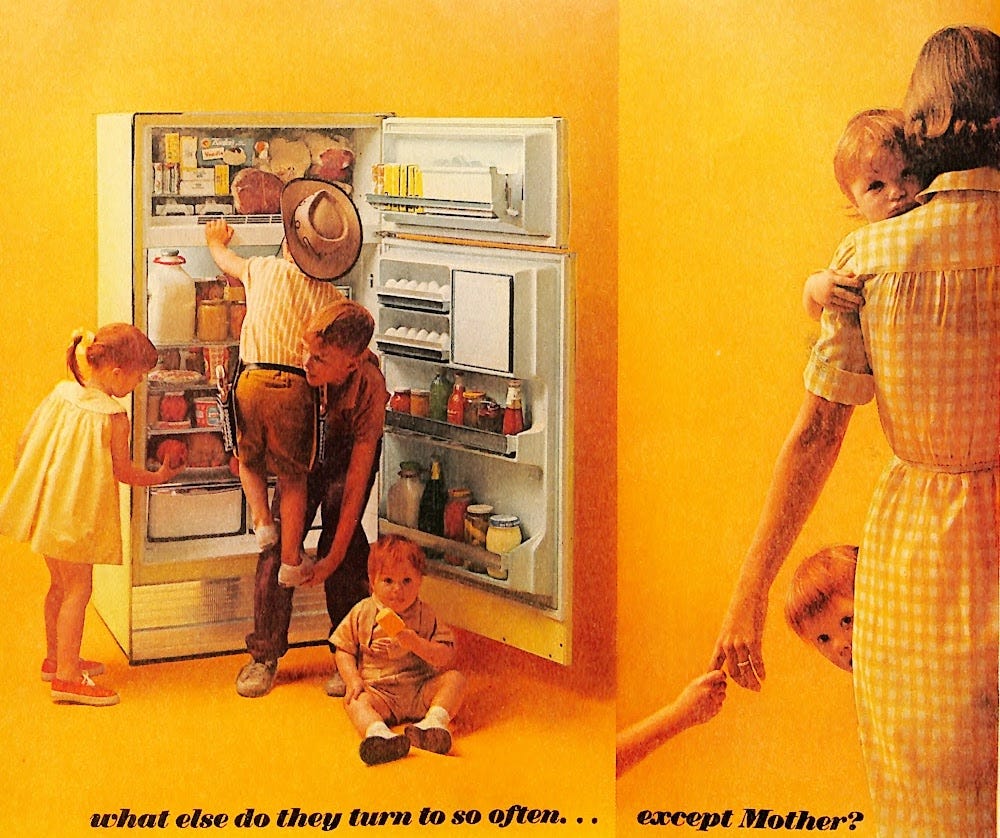

Sara: ALSO the idea of the “young, fertile mom” is so integral to momfluencer culture! And the marketing of ideal motherhood in the US. It’s really remarkable to consider how only the mothers who can uphold a certain kind of femininity, domesticity, and worldview get any [positive] attention in the US.

Nicole: This is so true, and I think it’s precisely why my own fixation with becoming a MILF didn’t start until my youngest child was no longer a baby but a bona fide kid. New motherhood is still, in its way, sort of sexy. A new mom is dewy and radiant and voluptuous; holding an infant to her breast, she signals to the world her fertility and fecundity. But once this phase has passed, she becomes, simply…a mom. And generally speaking, there is nothing titillating about a mom. A mom is used up and dowdy and irrelevant. She is, as you point out, no longer worthy of attention—and I think this is reflected in all the ways the needs of mothers and caregivers and families are systematically ignored in the US.

Sara: Amanda Montei recently wrote about women’s books (and stories about women’s lives) not appealing to men and this being a real problem (not simply a matter of book sales), and I so agree with you both. And I don’t see it changing any time soon. I guess I just feel depressed and hopeless about it lol and wonder if you see it differently.

Nicole: I wrote an essay for Poets & Writers recently about this very issue. One of the things I explore are the ways that books tagged as “female” tend to be marketed to women only, while books tagged as “male” tend to be marketed to both men and women. Manhood is treated as universal, while womanhood is treated as niche. This is a marketing problem, for sure, but publishers, like all commercial enterprises, take their cues from the culture in which they operate. And in this culture, it’s no longer very surprising for a woman to pursue “male” endeavors, but for a man to pursue “female” things still sounds the alarm bells. There are ways that our culture polices masculinity even more rigidly than it polices femininity.

I do wonder if the issue isn’t so much that women’s stories don’t appeal to men, but that men have been acculturated to believe our stories shouldn’t appeal to them—that being interested in such stories makes them soft or girly or effeminate. I share your skepticism that this dynamic will be changed easily, but I’m not entirely without hope--mostly because a number of male readers have reached out to me since my book was released to share, with honesty and vulnerability, the specific reasons why it moved them. Most of these men read my book because their wives or women partners pressed it into their hands, and I think this is a very good grassroots model of activism, in a way. At the bookstore events I’ve been doing, people will often ask me to sign an extra copy for their mother or daughter or best friend—and this is so wonderful! But how wonderful would it be, too, if I were signing extra books for husbands and sons and fathers and brothers?

I think I’ll start suggesting this during my author talks. I will say, “People, Mothers and Other Fictional Characters would make an excellent gift for Father’s Day!”