Jessie Spano deserves a You're Wrong About episode

Digging into millennial nostalgia with Kate Kennedy

I first fell in love with Kate Kennedy’s work when I listened to her EXCELLENT series on Rachel Hollis on her beloved pop culture podcast, Be There In Five. I’ve written about Hollis both here and in my book, and Kate’s analysis was critical to me sorting through my thinking on toxic positivity, the myth of meritocracy, and American individualism as it pertains to Hollis and other self-help gurus. Talking momfluencers with Kate was easily one of my favorite podcast gigs during book promo.

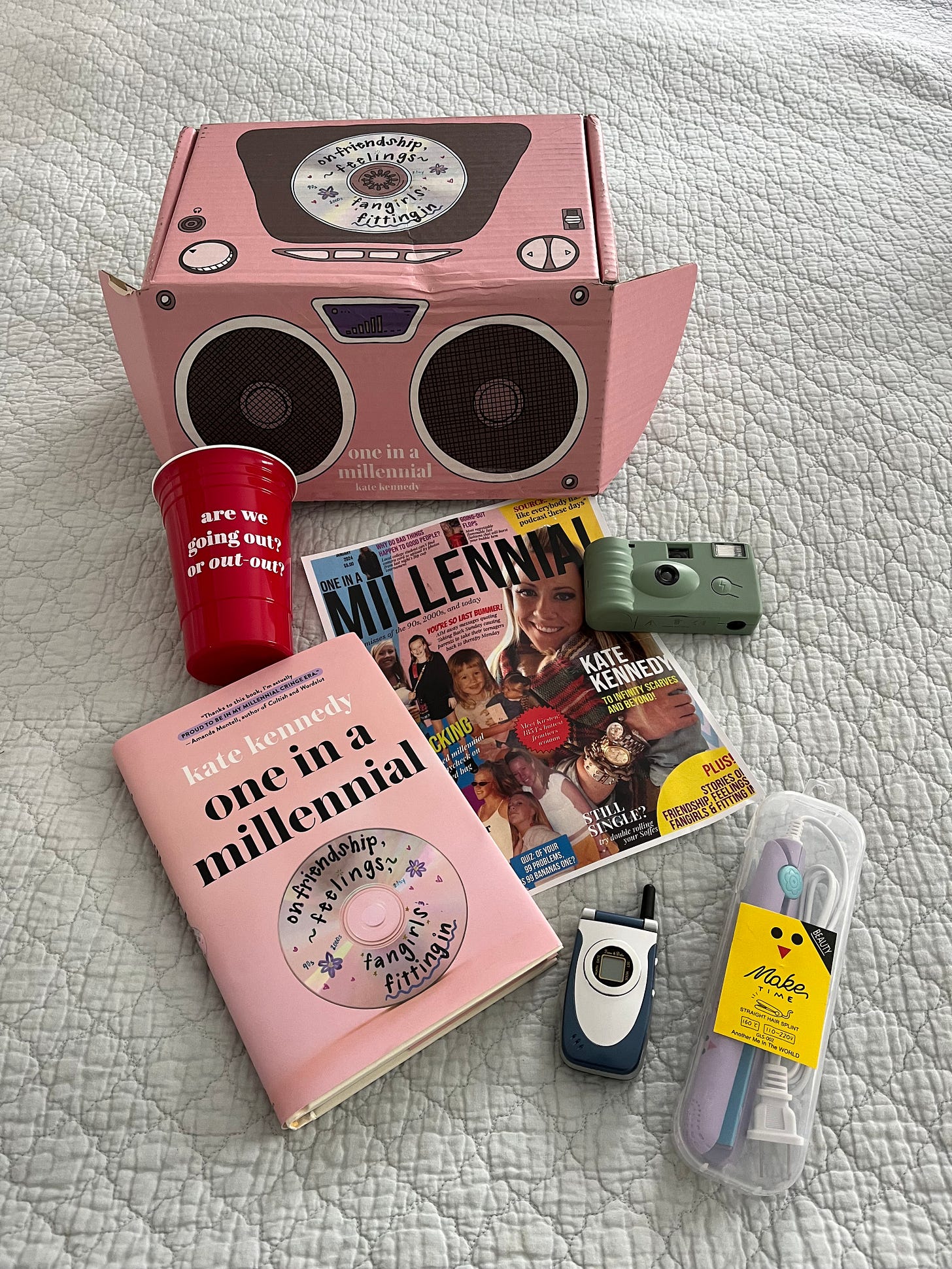

On her pod (and in her new book, One in a Millennial: On Friendship, Feelings, Fangirls, and Fitting In) Kate approaches all forms of pop culture in a way that relishes the froth and fun of, for example, your favorite Bravo show, but that also underscores what serious consideration of the The Real Housewives extended universe might reveal about sisterhood, gender, class, and race. Kate Kennedy loves pop culture, consumes pop culture, AND thinks (rightly!) that simply because something is enjoyable or popular does not exempt it from rigorous analysis.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my girlhood recently - and the movies, catalogues (J.Crew anyone?!), and cultural narratives that shaped it. Reading Kate’s book made me feel like I was hanging out with a kindred spirit that GOT IT, and also made me feel like I was hanging out with myself, or at least, the self I was before life took over. So give your inner girl a huge hug, put on your favorite going-out top, maybe throw an Ace of Base CD into the boombox (yes I’m an OLD millennial), call all your besties on your transparent purple phone, and get ready to laugh, cry, and have a fucking blast.

Sara: You write so beautifully about the mental real estate taken up by longing. You write about Vera Bradley bags, American Girl dolls. Clinique Happy, and so much more. Longing for things in order to convince ourselves that (as you write), a “new you is just around the corner.” To say I deeply relate would be a huge understatement, and I often write about how for mothers specifically, it feels good to hope that purchasing this diaper bag or this under eye cream or this “one shirt that goes with everything” will make being a mother in the US a little less shitty. You write “to this day, it’s still nice to believe sometimes” in the potential of consumerism as self-actualization. How has motherhood impacted your view on the relationship between capitalism and desire?

Kate: Oh, my gosh, I felt so many parallels to my adolescence and experiencing matrescence. Being in such a vulnerable stage of a major life transition where you lack confidence about your ability to belong in this new context. And when I was young, I didn't feel confident enough to lead with who I was. So the next best thing was to lead with what I wore, and allow brands and status symbols to precede me so I could be perceived as socially acceptable. And similarly, being a first-time mom, it's so weird to be a confident adult who has come so far, and then to be thrust into this new role at age 35 where I have absolutely no idea what I'm doing. And instead of sitting with that tension and giving myself grace, I just troubleshoot and shop because I can control the ability to buy things that would suggest I'm a good mother when I don't actually believe that I have the ability to be one.

Sara: It's so much easier to you know, panic shop for a sleeping contraption on Amazon when your baby's not sleeping than it is to sit with your new reality. You know, as somebody whose hours are dictated by the sleep schedule of a tiny human you are now in charge of keeping alive.

Kate: It's really brought to light the desire to constantly be fixing things instead of just letting them be what they are.

Sara: Do you think there's something to be said for retail therapy in moments when we feel really frustrated with big social inequities and feel powerless to effect any broader change? Like do you think moms can feel okay about buying the random shit at the random time? It's tricky.

Kate: Oh, yeah. I mean, I'm self employed. I didn't have a maternity leave. And, you know, even my pediatrician said something I found interesting. Like, the advice you're given is to keep the baby in your room the first six months, right? And she was saying like, well, that is based off research done in Norway, where there's ample paid leave, and where parents don't have to go to work right away to support the baby. But I was waking up with every single newborn grunt, every little rustle of movement, and it just wasn’t realistic. So when people are buying sleep training courses, and sleep sacks, and sound machines and the Snoo (which is a $1600.00 smart bassinet), a lot of it is because we can’t exist on so little sleep and still support ourselves and our families AND feel mentally sane. I think that consumption is absolutely tied to some of the shortcomings in how our society supports mothers.

Sara: I mean, they force us into consumption as a way to solve problems that should be solved with a social safety net. Switching gears - I texted a group thread the other day looking for a “kid appropriate movie with Lindsay Lohan Parent Trap vibes.” What is it that millennials love so much about the Lindsay Lohan Parent Trap? And can we talk about Meredith Blake as a maligned woman?

Kate: I think millennials love immaculate vibes. And Nancy Meyers is the patron saint of immaculate vibes. The pleasant aesthetics, the aspirational experiences, the interiors, the wardrobes, the dreamy careers, the vineyards. Her settings are relatable enough to understand but elevated enough to be aspirational and I think that as kids we just loved the energy of Nancy Meyers movies before we knew why we love Nancy Meyers movies. Meredith Blake is really interesting to revisit because she was written to represent a woman that wasn't fit to be a mother because she prioritized her career. She wanted money. She dressed a certain way. She was a little cold to children. She was presented as a villain for relatively benign reasons. As if she deserved to be drugged and sent out to the middle of the lake simply for not being particularly warm!

Sara: I also think it's interesting to compare her to the biological mother in the movie, who abandons one of her children and lies to the other???? I mean, the tenets of “good motherhood” are definitely worth unpacking in that movie.

Kate: It’s so neglectful and abusive and troubling. But when you’re watching the movie, you’re meant to be enamored by Elizabeth James and her warmth and her style and her chic London flat. Meanwhile, she’s fine not seeing her kid for like, 13 years?

Sara: It's bonkers. Okay, when I emailed you asking if you wanted to do this interview, I think I just said in all caps, DAMIEN RICE THE BLOWER’S DAUGHTER, as a way to communicate my enthusiasm for the book. Your specificity was absolutely mind blowing. And I know you consulted your old journals, but I still want to know how you dove so deeply back into your memory. You excavated so many aspects of girlhood I had forgotten I’d forgotten.

Kate: I did have my journal and my parents saved a lot so I had almost an archive to sort through. I also have an intensely observational nature. And I’d say I have a bit of a melancholic disposition, and as a kid, often the company I kept as was the media I consumed, particularly in the most trying or vulnerable times of my life. The music, movies, and TV I consumed nurtured the inner world I wasn’t outwardly presenting. So, while, you know, being friend-zoned or not invited to a party doesn't really warrant Damien Rice pathos, it was a way for me to feel validated in those moments. This is why meme culture is so effective. Memes are based on these things that are so incredibly specific. You see it you're like, Oh, my God, that's so me. I feel so seen. Without realizing that it's actually quite universal. It’s just not talked about enough for you to realize it's universal.

Sara: I feel like it's currently cool to view nostalgia with distaste. Like it's self indulgent, and maybe it’s harkening back to some sort of toxic good old days. But there's a reason nostalgia is fun.

Kate: When I was researching the book, I read that in the 17th century, nostalgia was essentially considered a psychological disorder. The root of the word has to do with soldiers feeling homesick. It wasn’t about hindsight, it was about longing. And when I really think about nostalgia, it feels like a homesickness for when I belonged to myself. I think girlhood is so special because it is an exploration of self before much is required of you. I think there's something so beautiful about the ways we spent our time before we assigned value to it. With this book, I wanted to honor all the times I was told the things I was doing would rot my brain. There's enrichment everywhere, and when I was young and participating in all these traditionally girly, “frivolous” things, I can identify a turning point when I learned that those were not things I should like to be taken seriously. And I kind of long for the time when I very unabashedly explored my interests. I think for a lot of people, nostalgia has a little bit more to do with connecting to who they were before the world told them who they had to be.

Sara: What resonates for me about girlhood is the space. You know, we are daughters, we are siblings. But we're not mothers yet. We're not romantic partners yet, and it does feel like a uniquely (and in some ways paradoxically) free time.

Kate: Absolutely. I read The Confidence Code For Girls, and there’s something called a confidence gap. Basically between the ages of nine and fourteen, girls’ confidence plummets whereas the confidence of boys in that same age bracket continues to rise. And one of the authors said something to the effect of - if life was grade school, women would run the world. I think it’s such a testament to becoming aware of how we appear to others instead of who we actually are, before we know enough about the world to be self-conscious.

Sara: Whereas I feel like living one's truth as an adult requires so much deliberate effort and excavation. I love that you explore this particular ease of identity in girlhood in the book. Okay, can we talk about Jessie Spano? When I read your chapter on Jessie, I was rather horrified about how my younger self had understood feminism through the men who created Jessie.

Kate: Yeah, Jessie was my way to explore the roots of my own elementary school misogyny. She often did and said things that could’ve had a positive impact on me. She was standing up for herself. She was trying to support women's equality efforts. She was pushing back against her male peers. But I didn't take away her strength. As a kid, I understood Jessie as a punch line. The manipulation of laugh tracks in this context can’t be overstated. Jessie would often make a really salient point about something, but AC Slater would immediately ridicule her and be like, you know, Why don't you get yourself back to the kitchen and the audience would roar. So if I'm 10, and I'm trying to understand how to behave and how to be accepted, I'm going to pay attention to who gets the laugh and who's the butt of the joke.

And the feminist was the butt of the joke. She was dismissed and disregarded. My perception of feminism stemmed not from Jessie but adult males’ perception of a feminist, because adult males were the writers and the creators of Saved by The Bell. Adult men were responsible for me thinking Jessie was nagging, grating, and difficult and that led to me not wanting to identify as a feminist, which was the case with a lot of teen media around that time. It was the Rush Limbaugh feminazi era. Right now, we are experiencing a cataclysmic regression of women's rights, and representation in media is kind of comparable to representation in public policy. The men in writers’ rooms and men in governmental offices write the jokes and write the laws that impact women based on their perceptions, not their lived experiences.

That’s why it’s so dangerous when there’s a majority of white men in charge of reproductive justice, something they aren’t qualified to understand nor will ever experience the effects of firsthand.

Sara: I think it’s depressingly common to not want to identify as a feminist as a girl - at least for our generation. As a kid, I viewed feminism as a big to-do over nothing, which obviously speaks to my own privilege and the holes in my education.

Kate: I’ve had a lot of trouble reconciling anger as I get older. As I age, I just feel more and more angry. And it's because I understand more about injustice. I see so many things I can’t fix, and when I think about men portraying feminists, it’s always about the anger. Like, Chill out - why are you so angry all the time? Feminist anger is positioned as a choice. But if you actually understand the many, many issues women face, anger isn’t a choice. It’s a reflex. And now I'm always operating at a low simmer. Don’t tell me I should be able to “take a joke.” Why should I have to?

Sara: Shifting gears again! I grew up as a Christmas and Easter Protestant. There were a few points during my childhood when we dabbled in regular church attendance, but in general, religion was not a huge part of my upbringing at all. HOWEVER, there was a brief stint during my adolescence where I threw myself into religion, attempting to read the entire bible, praying on my knees before bed, attending youth group, and even doing a church sleepover once. It’s hard for me to understand what exactly I was after back then, but this line in your book got me a little closer. You write: “I’m not sure if I was more influenced by celebs wearing purity rings in popular culture or the popular girls in the town I grew up in, but I remember thinking it was almost trendy to be this wholesome/mysterious hybrid of hot-girl devout.” While I didn’t have similar “cool religious girls” to emulate, I do think my flirtation with religion had something to do with a desire to be “not like the other girls.”

Kate: When I got involved with my Evangelical youth group, suddenly the very things that made me human were the things I was told to repent for. And when you're already insecure, and then someone tells you you're a sinner and your soul is damned, but there’s a way to fix it (religion), it’s a powerful combination. I think there’s also a pipeline of like, “good girl who doesn’t party or whatever and is generally cooperative” to intense devoutness. It’s a persona you can lead hard into that will give you lots of validation.

And in terms of the “not like the other girls” trope, I became involved with religion when I was learning from external sources that like shopping, sleepovers, gossip, and like, The Spice Girls was all embarrassing. The church labels those interests as frivolous, as being “of the world.” The church was very much at war with popular culture.

So my stance became, I don't need shopping. I don't need to go to the movies. I have my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. I'm totally surrendered and sweetly broken. And I think there was some internalized misogyny even in that. Yeah, I'm not like other girls. I'm saved. I'm unique. I'm different.

Sara: As we're talking, I feel like there's also something that religion promises in terms of like, bigness and significance. Like when you're a girl with a huge inner life and you're given limited avenues to express that inner life, I there's something tantalizing about the grandiosity of religion that you're not going to get from, you know, the fun of a Claire's shopping trip or whatever. Like, religion can be a funnel for the intense energy that girls aren’t really given a lot of outlets for.

Kate: Oh, absolutely. When you don't know a lot about the world, and your experiences are limited, the small things you're going through feel disproportionately intense. And you need a means to process it. If no one's acknowledging your inner world (and not many of us grew up with a good understanding of mental health), and if the default is “you’re broken, you’re a sinner,” religion offers you an outlet and a solution to the problem of you. The Father, Son, Holy Spirit, and it's like, Oh, great. I don't have to feel this. I don't have to process this. I can just lean into my brokenness and hope that I'll be saved.

Sara: I can’t not plug

’s Heretic at this point - it’s about both her experience with evangelicalism and the way evangelical ideology bleeds into so many aspects of modern life.Kate: Yes! In telling my story about purity culture, I really wanted others to see the ways in which purity culture impacts all of us, and how the influence of people pushing their religious agendas is everywhere.

School dress codes are the ultimate example of this. Dress codes prioritize boys’ education over girls’ education. Abstinence-only education! There was so little information on how to safely explore sexuality and our own pleasure. It was all a focus on our supposed responsibility to control how boys responded to us and our bodies. Whether you learn that in the chapel or in the gymnasium, it's pervasive and it leads girls to tie their self worth to their perceived purity.

Sara: Ugh yes. Switching gears YET AGAIN because your book is so beautifully multifaceted! I ADORE - absolutely ADORE that you wrote about the magic that is “getting ready.” In general, I prefer being 42 to 24, but I do desperately miss the indelible feeling of POSSIBILITY inherent to the experience of getting ready with friends even if the actual “going out” party was a bust. I guess the idea of infinite possibility is also something reserved for the very young (in some ways), but I find myself searching for an alternative - or at least a new version - as a wise middle aged lady lol. What do you think? How can we feel a sense of adventure as grownups? Or maybe - what do you think the desire for newness and adventure really says about people?

Kate: The magic of this era of life is that you are in the same life phase as your girlfriends. And you don't know at that time that it is about to fragment in ways that will make you unrecognizable to each other - because women become defined by who they are to other people. We were facing so much insecurity and uncertainty and we poured our energy into building each other up. Inside the walls of a pregame, we could control how we felt about ourselves through community. And even if the night would be an utter disaster, something about the hopefulness found within the walls of the “getting ready” is incredibly electric.

Sara: Yeah, I’m remembering everybody piling onto a bed to watch one person try on like seven different outfits. An external male gaze could look at that scene and determine that none of this matters. We all know the various going out tops looked more or less the same, but the attention we devoted to each other is a really specific form of love.

Kate: Absolutely. It was magical. And this is why I'm a big big believer in “the girls trip.” In going out of your way to honor leisure time with the people that know you best and to sit around and talk and laugh like you once did before life got a lot more complicated. I know that sounds really simple but it’s something I've tried to do more in recent years - prioritizing and maintaining friendships that make me feel like myself.

Sara: Last question. The idea that serious analysis of pop culture is pointless or frivolous seems to me to be such obvious bullshit that it’s hard for me to even really engage with such a viewpoint. I’m curious if you think that perspective has gained or lost steam through the years. When I first started pitching cultural analysis of momfluencers, very few editors were interested, but now, every other nonfiction book I want to read is a deep dive into something that might seem initially surface-level or unworthy of intellectual examination.

Kate: I think the cultural conversation many of us experience within the media content we consume is very different from the conversations we have in our actual lives. Maybe in some cultural circles, serious analysis of pop culture is normalized, but I still get made fun of for liking Taylor Swift by extended family members. There are still people in my life who think my job is unimportant or merely an example of “overthinking” things. So I think these things are more widely accepted in theory, but interpersonally we experience a lot of tension and still feel obligated to defend what we find interesting.

Sara: Have you fully shed those vestiges of like, I should like different things or me liking something dictates something incontrovertible (and shameful) about my personhood? Or do you still carry out a bit within you?

Kate: Oh god yes. It's evidenced in how uncomfortable I feel when people ask me about my job. I'm very, very proud of my career and what I've built. But I also have so much anxiety when people ask me what my book’s about because depending on who it is, and whether or not the book is for them, they're going to make me feel as small as possible. I would love to not be affected by it, but I'm a sensitive person who wants to be understood. I just think moving through a world filled with a lot of judgment and misogyny will make me forever try to contort myself into a version of me that the person I'm talking to is comfortable with. I don’t endorse that way of being! But it is my default setting.

Sara: RELATABLE.

Kate: I want so badly to be a person that's like, whatever, haters gonna hate. But I think some of us aren't wired that way. I also think it's healthy to care what people think about you and even though I wish I could completely shed all of my self conscious tendencies, we were conditioned to have these tendencies and I don't think we should make things worse by beating ourselves up for not being totally transformed. We have good reason for some of our reflexes.

I'm really fascinated by the idea that girlhood is more expansive than womanhood and it's easier to be yourself. I feel the opposite and I wonder how much the difference is related to whether someone is a mother and in a heterosexual relationship. You guys talked about how women are defined by their relationship to others, and if you're in those roles with strong social expectations it makes sense that you would feel limited by them. Whereas I'm over here feeling like I can do and be whoever I want now that I'm an adult and not under the control of parents, teachers, etc. As a girl i felt trapped by strict rules and didn't know it was okay if i broke them, (will anyone ever love me if I don't shave my armpits?) but as an adult I know i can do what i want and the judgement of others doesn't really matter. My wife has no expectations for who I'll be and I'm not defined by my relationship to her because there isn't any dominant social narrative for how lesbian marriages should go.

I'm a baby Gen-X so I'm a few years older than you guys but I hate watched SBTB every day on TBS after school with my friends and I so wish we could go back and give Jesse Spano and Lisa Turtle the respect they deserved. Poor Lisa, beautiful, popular and rich and constantly gaslit for not reciprocating gross-ass Screech's obsession with her.