To do: groceries, soccer carpool, divine transcendance

Finding real wellness in the wellness industry with Rina Raphael

Earlier this week, I wrote about the dubious (if not wholly bogus) attempts made by companies like Botox to endorse their products as vehicles for self-care and wellness for women (and, more specifically mothers needing some “me-time”). Here’s a quote from the piece.

Mothers should absolutely do what they need to do to get through the day. But marketers deliberately working to keep us trapped in a maelstrom of discontent and insecurity by condescendingly selling Botox to mothers as “self-love” don’t care about mothers loving themselves. Their livelihoods depend on the fact that we don’t.

As moms, we are all very well accustomed to being told by capitalism that our maternal identities make us perfect consumers of this sweatshirt or this whimsical floral dress or this clean beauty concealer or these paper towels or these baby cardigans or that workout subscription for “getting our bodies back” (after creating actual human beings within those bodies).

And while capitalist consumerism has urged moms to buy shit to soothe our despair, our ennui, and our loneliness since time immemorial, now we also are incessantly bombarded by the noise of the wellness and self-care industries which (like their BFF capitalism) also want us to spend copious amounts of money. But they want us to spend that money for ourselves; for our inner peace, for our probiotic flora, for our spiritual equilibrium, for our gut-health, for our inner children, for our hip-flexor flexibility, for our divine womb voices.

It’s not about CBD oil companies making a profit off of mothers’ burnout, it’s about us as individuals attaining transcendence by way of ice-rollers and ashwagandha teas - even if the rest of the world is burning as we pursue true presence ensconced in our sensory deprivation tanks.

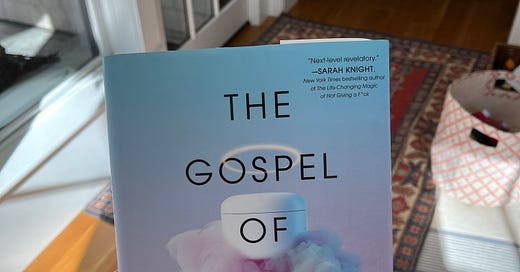

In her new book, The Gospel of Wellness: Gyms, Gurus, Goop, and the False Promise of Self-Care, Rina Raphael writes this about women and mothers trying to keep their heads afloat in the currents of commodified wellness and self-care.

Their life is nonstop emails and baby tantrums; they have two jobs but the respect of one. This is what the renowned sociologist Arlie Hochschild in 1989 termed “the second shift,” by which Western women inherit a double-career life. They’ll work a full day at the office, commute in traffic back home, hang up their coat, then run into the phone booth to transform into Superhousewife. The current hyperproductive and performative nature of American life is likely to blame. We’re on a constant treadmill of doing way more than a normal human would have aspired to do until recently: attain career success, birth two kids, achieve a slamming body, cook like Ina Garten . . . You get the idea.

And for women coming of age as mothers in the age of social media and intensive mothering, we also have to hone our performances of “good motherhood” until everything sparkles. Our floors, our kids’ teeth, our dainty gemmed stacking rings, and maybe most especially, our maternal joy and unshakeable maternal authority. As moms traversing both momfluencer culture and wellness culture (the two cultures, are, of course, often tightly interwoven and interdependent), we are expected to do it all and feel zen as fuck about it because of course, we meditate before the kids (or the sun) are up and overwhelm can be cured by a “mindset shift” and structural inequities can be Palo Santo-ed away.

The Gospel of Wellness is a nuanced, validating, enlightening, and necessary antidote to the confounding world of Instagram ads, momfluencer gurus, and Botox for Busy Moms we’re all trying to survive, and I hope you enjoy my conversation with Rina as much as I did!

Sara: I'd love to know how you defined self-care and wellness to yourself before you started working on the book.

Rina: The wellness category spans nutrition, fitness, movement, mental health, spirituality. It's a really, really broad categorization. And because of that, the wellness industry is able to propel a whole bunch of products and sub-sectors into the term “wellness.” I personally understood it as working out every day, buying only “non-toxic” and organic, and tracking everything. So much consumption, self-optimization, and productivity pressure. It was pretty rigid and it ended up stressing me out. Or it made me obsessive: If I didn’t get “enough steps” on my Fitbit, I’d punish myself. “Clean” eating gave me disordered eating.

Real wellness is simply all the ways we need to individually feel and be better; it encompasses all the ways we can take care of ourselves, which is a worthy endeavor. And there's a long, long history of how the wellness industry originally started, and the early iterations of wellness were very different from the wellness industry today. Unfortunately, the market has devolved to sell us a slew of interventions, non evidence-based treatments, and products that are not necessarily about actually moving, eating well; all these things we need to be truly well. And it's also very, very prescriptive, and it’s often very generalized. I mean, how you need to feel better is different from how your friend, your mother, or anyone else needs to feel better.

Sara: And what about self-care?

Rina: I dig into the origins of the term “self-care” in the book, and the term really stemmed from more radical and political roots, which in turn, stemmed from the medical and healthcare system. Self-care also has roots in political community organizing. But today, when the average person thinks about self-care, they’re imagining bubble baths, skincare masks, or Sephora shopping sprees. And that's not what that term originally meant. A lot of people get a little offended by the subtitle of my book because they say, “What's wrong with self-care?” There's nothing wrong with self-care, real self-care, but real self-care is different from being told that you individually need to not only take care of yourself, but also, you need to buy a whole bunch of stuff. And not just any stuff, very particular, expensive stuff. That's the problem of how the market has evolved. And that's my criticism.

I am, of course, in favor of fitness, movement, nutrition, meditation, etc, but it's the messaging that's becoming corrupted. For example, I take issue with workplace wellness programs, where they just keep telling their employees, Oh, you're stressed, you're not sleeping well, okay, then you should download this app and you should go to this yoga class. Maybe it’s your job responsible for the stress!

These programs don’t address the root reasons of why we're so stressed, so unwell, and so lonely. Today, “self-care” puts the onus on the individual. And the problem with putting the onus on the individual is that it sets you up for self-blame, because every time you're stressed or you're not “zen enough,” you are trained to think, Oh, I didn't do enough self-care or take good care of myself.

You aren’t encouraged to look at the real reasons you’re stressed or exhausted, which might be because there are not enough maternity benefits in this country. There aren't childcare policies. We have addictive tech and a 24-hour news cycle. There are so many reasons why we're overwhelmed. But instead, commodified self-care and wellness just tell you to treat the symptoms. It's almost like gaslighting. We’re being sold individualistic remedies and often ignoring what’s required: systemic solutions to big issues.

Sara: Totally. It’s like putting a Band-Aid on a gaping chest wound, you know? I also think both wellness and self-care are really aggressively marketed to mothers as a way to deal with the existential hell of being a mother in America. Like, You’re tired? buy this clean beauty eye cream that’s been made from lavender hand-picked in an idyllic field somewhere so you look more rested. That cream won’t meaningfully help you deal with the exhaustion of being up all night with your newborn. Universal healthcare providing you with a postpartum doula, on the other hand, would help with your exhaustion.

Rina: Right. I have a chapter in the book called, Why the Hell is the Advice Always Yoga? And I wrote it because I was so frustrated with people telling me every time I was stressed out for legitimate reasons (just like many moms in America and many women in America) to simply do all of these self-care rituals. And they're all temporary. I can go and workout or I can go do another meditation but my problem is still waiting for me when I get back. Self-care almost seemed to become another obligation, another thing I was supposed to do.

I delve into how much work we’re doing towards “good”health. And it was really inspired by so many moms who told me like, I have all these things I need to do and I have no support. Not even just community support but institutional support. And now I'm being told I need to meditate my woes away. Becoming perfectly calm and centered became another thing on moms’ to-do list.

And it's part of our culture of perfectionism, right? God forbid a woman shows her anger. God forbid she says, “This isn't okay,” or “The system isn't working.” No, instead it's on you, the individual, to make sure that you're calm and centered enough for everyone else around you.

“To be a woman today is to be stuck in a loop of unrelenting maintenance.” - Rina Raphael, The Gospel of Wellness

I do want to be really clear, that real wellness is separate from what we're being marketed right now. And I go into all of the marketing strategies and manipulative tactics that really prey on our vulnerabilities and aspirations. These strategies really get at every pain point and everything we want and hope for the future. The book also tracks my experience not only being a wellness devotee but a wellness industry reporter. I just want to say to other women feeling lost in all of this, like, It’s not your fault if you fell for any of these fads because I fell for them too. The marketing is just too good, it’s too clever.

Sara: Yeah. I underlined this line in the book: “To be a woman today is to be stuck in a loop of unrelenting maintenance.” And I mean, yes, yes, yes, 100 times yes. You write in the book about the exhausting pursuit of health and healthism, and I mean, once a woman has kids, not only is she expected to unrelentingly maintain her own wellness, (whatever that might mean culturally and personally), but now she has to do it for her family too. Because despite some progress in gender egalitarianism within the home, the mother is still largely presumed to be the one buying the food, making the food, buying the cleaning products, etc. After researching the book, did you see a clear distinction between how the wellness industry impacts women and moms and how it impacts men?

Rina: So, first of all, women interact more with the medical industry. They go to the doctor more than men starting from when they're teenagers (visiting the gynecologist, for example). And as you mentioned, women and mothers are still burdened with the second shift. But also, if you're to believe the polls, women are more stressed than men, particularly because they don't have institutional support and they don't have child care policies or you know, whatever it is, pick your poison.

I have an entire chapter on the fact that a lot of women are coping with health conditions and feeling like they're not getting what they want out of their doctors’ visits. Some feel gaslit, some feel like they're ignored, and others are just faced with doctors who shrug their shoulders and say, I don't know what to tell you. And that's partially because women's health conditions have been underfunded and under researched. So of course women are looking for alternative therapies or looking for different communities where they can find that support. And sometimes, out of desperation, women will find a treatment out there that doesn't have scientific evidence, but they’re willing to try it.

All of the pressures placed on women within our society to look and be certain ways can be easily disguised under the term “wellness.”

And then there’s the problem of this industry preying on women. This happens when you see diet culture snuck into wellness. A diet masquerading as like, “healthy eating” or “clean eating” when it’s really just another restrictive eating protocol. This is when you see supplements that are marketed as “healthy,” but if you read through the marketing, it's really about like, looking better or thinner. All of the pressures placed on women within our society to look and be certain ways can be easily disguised under the term “wellness.” And the book really tracks how language is being twisted to basically serve up these old ideals in different outfits.

Sara: I think a lot about how girls are raised to pursue motherhood as the be-all end-all of their “womanly experience.” Women are assumed to be “naturally” good at mothering. And we're really given no guidebook for how to do it. So it's only natural that once we become moms, we are thirsty for somebody to tell us the right way to do things. Especially because the ideal of motherhood is held up on such a pedestal. Not only do we have to be mothers and keep our kids alive, but we have to be “good moms.” And in certain subsets of momfluencer culture, I see so many white woo-woo wellness moms talking about gut health or mold toxicities or chemical sunscreens or vaccines and connecting their “research” and “authority” to their performances of ideal motherhood. I just find the relationship between ideal motherhood, whiteness, and the wellness industry consistently fascinating. All three things are constantly feeding into each other.

Rina: Every day there's another study saying, This is good for you. This is bad for you. Avocados are good for you on Monday but Friday, they're bad for you. People are exhausted. They’ve been fed so many different protocols, so many sets of conflicting advice, that they’ve lost trust in institutions. And they're just like, Okay, someone just tell me what to do already.

And after speaking to hundreds of women across the country, a lot of women are just looking for support. They feel all alone. They don't necessarily have a community of people they can turn to and when it comes to big life transitions like motherhood, they don't have someone they can readily depend on. You know, we don't live in villages where you can just go next door and say, What do I do? So they need to depend on experts. And a lot of them are influencers. So much of my book tracks what's going on with the loneliness epidemic. It’s why some women are either going to their therapist or their Soulcycle instructor for advice. And this isn’t because they don't have friends. They do have friends, but everyone is so busy. They don't have time to get together with a friend and yack their ear off about what's going on in their marriage, or what to do with their child who might be dealing with some sort of an issue. Everything has become so commodified and outsourced. In her book, Self-help Culture, Wendy Simmons talks about the professionalization of advice. We used to be able to go to friends and family members for advice. But once families got smaller and more isolated, women entered the labor market, and America got more individualistic, then we had to start buying our advice and guidance. And that's the tragedy of America.

There’s also the fact that your doctor doesn't necessarily have time for you, right? The average doctor's visit is 17 minutes long, and I think you're interrupted at around seven minutes. And it's not doctors’ fault necessarily. It's the system's fault. I spoke to plenty of doctors who said, We wish we could spend more time with patients, but that's not incentivized. We’re forced to work in this hurried system where you're paid by the number of patients seen.

So it’s probably a lot easier to find guidance and health advice on social media from an influencer who is posting several times a day and can maybe DM you and with whom you can forge a personal relationship.

Sara: It's also complicated because a lot of the time, as you pointed out, women have been really mistreated by the mainstream healthcare system. I mean, if you think about Black maternal mortality rates, there's a very good reason Black moms might not want to give birth in hospitals. But often this valid fear is co-opted by white women guru types. There are so many (white) “free-birthers” who preach against C-sections and other necessary medical interventions, claiming they’ll destroy chances of a healthy attachment between mother and child. I mean, really harmful stuff. So it seems like some wellness trends are rooted in a real need for better options but become diluted and coopted in frightening ways. Why do you think this happens so often in the wellness space?

Rina: A lot of the wellness movement is built upon legitimate critique. A pushback against a disappointing healthcare system, pharmaceutical scandals, distrust of Big Food, a whole bunch of different entities. And people are right to push back, because in many cases, people have been wronged by these systems.

However, just because there are real issues within the medical industry, doesn't necessarily mean that alternative medicine does have the answers. But when you're not getting the empathy you need, when you’re not getting the care you need, you might look elsewhere.

If people are getting more out of Gwyneth Paltrow than their own doctor, then we have a problem with medicine, right?

There’s a chapter in the book called A Plea to be Heard, and it’s all about women arguing that they need someone who will listen, and this need to be heard is really important. And if the medical industry doesn’t address this valid need, they will continue to lose patients. If people are getting more out of Gwyneth Paltrow than their own doctor, then we have a problem with medicine, right? And listen, if you go to a doctor's office and you bring up some symptoms, oftentimes you'll get a probability, not always assurance. But as one one doctor said to me, “Most wellness seekers are uncertainty avoidant.”

A lot of these gurus promise that they will definitely cure you of this condition. They will definitely help you with these symptoms. They will definitely make you feel better. America is a highly optimistic country. We want to believe in certainties. And this is also how the wellness industry preys on our vulnerabilities and our deepest desires. It's a lot more enticing to follow someone who says, I'll definitely get rid of this problem for you versus your doctor who says, Well, there's a 30% chance you might get better, but you might need to do X,Y, or Z first. Often, doctors’ advice is complicated and deals in shades of gray. There are rarely any magical pills. But gosh, supplement brands have plenty of those magical pills.

Sara: YES. I always come back to motherhood, but the promise of certainties is so tantalizing for mothers in particular. Say your toddler is having meltdowns at bedtime every night. If somebody told you it was as simple as cutting gluten from the toddler’s diet, um, you will cut gluten from that screaming toddler’s diet! You want to believe something will fix the problem. And you’re right – a doctor is much more likely to mention bedtime meltdowns as a symptom of any number of causes. It could be a developmental delay OR it could be totally typical. Often you leave the pediatrician with a vague book recommendation feeling like, Well the doctor’s answer is Who Knows, but I’m fried and want to sleep so I’m listening to the wellness influencer and cutting out gluten.

Rina: Yeah. Also, I want to be clear that there are definite experts offering really great solutions for people online. Not all online resources are inherently exploitative or suspect. But when it comes to the obvious hucksters, they thrive because America loves a quick fix, especially one we can buy. And I don't blame the average woman because when you are that stressed out, when you feel like you have so little support, you don't necessarily have the time to think through all of the complications, or to look into what you're buying. And oftentimes, when you're stressed, you're just more reactive. So I understand why people buy into these things. It's the same reason I bought into them. I was stressed out. I was like, Oh, someone has a solution. I'll try it. What's the harm?

But there can be harm, especially when it comes to medical conditions. When someone suffering from a condition buys into scam supplements or non-evidence based practices, they’re not just wasting money. They’re potentially being robbed of real therapeutic treatments that could actually help them. Or, in some cases, they’re delaying medical care which can have devastating consequences.

Sara: So many of the more harmful momfluencer grifters are big proponents of their supposedly innate maternal authority trumping all else. If you’re buying into a belief that the mother (and the mother alone) should have supreme moral authority of her children’s souls, her children’s physical wellbeing, then of course she should also be the one “doing her research.” And I just find this so problematic in so many ways. I don't think it's great that we're encouraging this individualized, insular model in which the nuclear family (and the mother within in it) is sacrosanct. Also, we shouldn’t expect mothers to be experts on everything! I'm not a chemical physicist or whatever. Like, I should not be tasked with doing research about the products that I'm cleaning my kids’ bodies with, or you know, the toothpaste they're using. We should have protections in place. We shouldn't be tasked with doing all this individual research. You had a phrase in the book – “the safety burden” - can you talk about that?

Rina: I don't recommend “doing your own research” about many things, because the average person simply doesn't know how to read or evaluate studies. You can find a cockamamie study for anything. You could probably find one about tobacco and nicotine being good for you if you really wanted to. You can find a study saying homeopathy works, and ignore the other thousand studies that find there’s very little scientific evidence behind homeopathy. Michelle Wong of Lab Muffin Beauty talks about “science-washing.” There are all these brands and influencers manipulating or cherry picking studies to say Oh, this works. Look at this study. And people hear the word “study” and see scientific language as confirmation that something is legitimate. As soon as something sounds like Bill Nye, we’re sold.

They were made terrified of ingredients like formaldehyde being used in a vaccine without understanding that there’s more formaldehyde in an apple.

We’re also taking advice from people who aren't necessarily even experts in the fields to which they claim expertise. If you are concerned about your beauty products and interested in clean beauty, you should really be taking advice from a toxicologist or a cosmetic scientist, not necessarily a dermatologist because a dermatologist isn't necessarily versed in toxicology. And I wouldn't even trust one expert because what if that one expert is Dr. Oz? Make sure the expert is someone respected in their field and whom other experts refer to. You also want a consensus formed from specific experts in specific fields. Dr. Danielle Belardo of the podcast Wellness: Fact vs Fiction has some good advice: check the major society guidelines for any issue or medical condition you’re curious about. If a certain influencer is advising against expert scientific consensus – and using emotionally manipulative language – you should probably refrain from taking their advice.

Sara: Can we talk about clean beauty?

Rina: It’s everywhere, right? The messaging is ubiquitous. It's in every woman's outlet, on social media, in Sephora, everywhere; clean, clean, clean. But this term “clean” insinuates everything that isn't labeled clean is therefore toxic. And that's such a dangerous, dangerous concept. It's making people terrified of their products or, in very rare worst cases, leading to chemophobia. I spoke to some anti-vaxxers, and when I tried to get at where it first started, they said they were influenced by the simplistic, fear-mongering messaging of the clean beauty movement.

Sara: Whoa.

Rina: They were made terrified of ingredients like formaldehyde being used in a vaccine without understanding that there’s more formaldehyde in an apple. They just didn't understand the basics of chemistry and it’s not their job to understand those things! The clean beauty industry does have some fair points, but it is a lot more complicated than they're communicating to the consumer. But hey, fear sells.

Sara: This also shows how class factors into our conversation about wellness. Because if the onus is on the individual consumer to research what may or may not be beneficial or healthy to consume or use on one’s body, we’re essentially assuming that only people with the most money and the most time can afford to this type of research. And by extension, only the people with the most money and time are worthy of being the “most well.”

Rina: Right. It's a prosperity gospel to some degree.

Sara: You mention The Class in your book, and I’m a fellow Class fan. It can be a little goofy, and it’s definitely woo-woo, but I love it. And you argue in the book, that, like, it does feel good to jump around and yell for an hour. It feels good. And even if the effects of The Class don’t make the rest of your day feel good, there is value in doing something that makes you feel good even temporarily in such a broken word. I guess I love this example because it really encapsulates one your central points which is that wellness is not all bad, nor is it all good. I mean, mothers are burned out. Ultimately, what we need is not another workout regime, but systemic change. But in the meantime, it’s nice to feel good via some deep breathing, downward dogs, and some jumping jacks.

Rina: Definitely. And it's funny. I talked to many women who told me the wellness movement actually gave them the language to take time for themselves. Like, women saying, “I need to take a walk for myself. It’s my self-care. It’s good for my mental health.” I think it's ridiculous that we even need language to get an hour to ourselves, but I thought that was an interesting potential positive coming out of the industry.

Sara: That is so interesting. Like, even though wellness and self-care have become so commodified, they’ve maybe at least empowered women to put words to their own needs.

Rina: Yes. And I also think that we culturally focus more on mental health than we have in the past. I see a lot more people (especially since the pandemic) cite exercise, for example, as being critical to their mental health (versus doing exercise to attain a certain body type).

Sara: We sort of touched on this earlier, but one of my biggest issues with the wellness industry is the focus on self-optimization and the complete lack of focus on community care and collective care. Circling back to The Class, it’s nice that I can feel better for an hour, but until ALL mothers are able to feel good, we have a problem.

Rina: Right. And this is one of my major critiques. Wellness (as an industry) is hyper individualized. Everything is about what you yourself can do on your own. So, we sit at home riding our Peloton, we take our bubble baths alone at home. Even if you attend a boutique fitness class, your’e not often interacting with people meaningfully.

One of the biggest pillars of real wellness is social support and community, and that's somehow been completely ignored by this industry. The origins of self-care were much more politically activated and much more about communal care. How can we band together to deal with systemic issues and care for each other together? versus what we're being told now, which is that you’ve gotta take care of your mental health and everything else, all by yourself.

Sara: Did anything surprise you in researching and writing the book?

Rina: I was a wellness industry reporter who propped up a lot of the companies that I now criticize within the book. And writing the book really made me reflect on the ecosystem that we're in and how it’s been impacted by media coverage. That’s not the sole reason, of course. There’s also the rapid proliferation of misinformation on social media, eroding trust in institutions, and so on. But the people writing stories on wellness trends are not expected to speak to the necessary experts, and you find so many wellness stories in the fashion or style sections, not in the health or science sections.

And in the relentless pursuit for health, whole communities are left out of the conversation, and these communities are made to feel like they’re endangering their families, or that they’re not good enough.

Wellness is treated a lot more like fashion these days. Think about the last decade:first it was bone broth, then green juice, then it’s functional elixirs, then it’s kombucha, then it’s CBD seltzer or activated charcoal. These are all fads. And when people say, like, “What’s so bad about fads? All sorts of things are fads,” I say, “Yeah, but we’re talking about health here.” And in the relentless pursuit for health, whole communities are left out of the conversation, and these communities are made to feel like they’re endangering their families, or that they’re not good enough.

In the book, I write about organic produce. On various Facebook groups and message boards, I found so many women saying, I can't afford organic produce for my whole family, so I buy organic for the kids and my husband and I eat the cancer-causing shit. That’s so damaging! Organic better refers to a farming process and doesn’t necessarily mean organic produce is healthier or more nutritious than conventional produce , But just the idea that if these women buy a non-organic apple, something bad is going to happen. This is such a toxic idea.

Many dietitians also told me that some lower income groups avoid the produce aisle altogether because they’re terrified about conventional produce pesticides but they can’t afford organic. This type of fear mongering is counterproductive and actively harming certain groups of people. Organic is a complicated topic I get into with help from toxicologists and food scientists, but suffice to say, organizations like the EWG (which are heavily funded by organic companies) are manipulating the science to terrify consumers.

One of my main hopes with the book is that people might be able to relax a little bit more. Because right now, there’s so much heightened anxiety about health. We’re fetishizing health instead of naturally folding it into our lives.

Damn, this book sounds good. I wish I could get back all the money I’ve spent on “clean” beauty, organic produce, grass-fed meat and supplements.